Free Internet Calling Archives

Free Internet Calling Archives

FAQ

How do I make a call with Cloud Sim?

Open the app and select a contact or key in the number in the dial pad.

Do I have my own number where people can call me?

You can easily set up multiple additional mobile numbers that you your contacts can call you on. This allows you to keep you main number private, create international presence and also save on roaming fees when you are abroad.

I cannot make a call

There are a variety of reasons you may not be able to make a Cloud Sim call.

- Are you connected to the internet? Cloud Sim requires an internet connection. Please ensure your device is connected via Wi-Fi or mobile data.

- You have no free contacts – invite your contacts to Cloud Sim so you can call and message them for free.

- You have no credit – calls and SMS to non-Cloud Sim users are chargeable so you need some credit. You can buy credit here.

- You are not dialling correctly – All calls should be dialled in international format.

- You are dialling a special service, premium rate, satellite or IP numbers. Cloud Sim will not connect these calls.

I cannot receive a call

To receive calls your contacts need to call one of your Cloud Sim numbers. You can easily share your number. From the app Home Screen click  and ‘Share my number’.

and ‘Share my number’.

The person I am calling cannot hear me

You may need to allow Cloud Sim to use your microphone.

- On your iOS (Apple) device

- Open your device ‘Settings’

- Click ‘Privacy’

- Click ‘Microphone’

Toggle Cloud Sim to ‘on’.

I cannot hear the person I am calling

You may need to allow Cloud Sim to use your microphone. Check your general phone settings.

Can you explain the various call types?

- Free Calls – Calls between Cloud Sim users are routed totally across the internet.

- Wi-Fi/mobile data – Calls are routed over the Internet via your Wi-Fi or 3G/4G data connection to Cloud Sim, where we connect you to the telephone network and the person you are calling. Use this method when you have a good internet connection.

- Local Access – This method is only used when you are in your home country, using a SIM card from that country. Cloud Sim connects using your local GSM minutes. This is a great way to use Cloud Sim, especially if you are out of range of a Wi-Fi hotspot and also have a monthly bundled minutes allowance.

- Callback – You click to call your contact as normal and Cloud Sim seamlessly ‘calls you back’ then connects you to the number you are calling. For use in countries where Local Access is not available. Callback calls are slightly more expensive as there are two parts to each call. The app requires a very small amount of data to initiate the call.

Can I call emergency numbers?

Calls to emergency numbers are not permitted. Cloud Sim is not a replacement for your telephone.

Can I call non-geographic numbers with Cloud Sim?

Premium numbers are blocked although some non-geographic numbers can be called. Contact customercare@cloudsimapp.com for details and rates.

Can I use Cloud Sim instead of my SIM card?

Cloud Sim is an over the top service. You must have a mobile phone number from a recognised mobile provider in order to to validate your account by SMS. You can then use your Cloud Sim account on tablets without the need for a SIM.

How can I make an international call?

With Cloud Sim all calls, including local calls, should be dialled with an international prefix. To dial an international number you need to:

- Dial 00 or the symbol “+” to get the international service, then the international code

- Identify the international dialling code for the destination you are calling. 44 for the UK, 33 for France, 971 for the UAE, etc

- Dial the number you wish to call, usually without the first zero

A lawsuit is threatening the Internet Archive — but it’s not as dire as you may have heard

The Internet Archive (also known as IA or Archive.org), home to the giant vault of internet and public domain history known as the Wayback Machine, is currently facing a crisis — one largely defined by misinformation. A group of publishing companies filed a scathing copyright lawsuit earlier this month over the IA’s controversial attempt to open an “Emergency Library” during the coronavirus pandemic. Ever since, confusion about the scope of the lawsuit and its potential impact on the IA as a whole has stoked fears of a crackdown on the IA’s many projects, including its gargantuan archive of the historical internet.

But much of that fear seems to be exaggerated. And while the lawsuit is a big deal for advocates of an open internet, it’s probably not the existential threat to the IA that you may have heard it is.

The Internet Archive is a preservation project — but some publishers think it’s piracy

The Internet Archive is a nonprofit internet archival organization. Founded in 1996, it digitally preserves more than 1.4 million books and historical documents, as well as cached versions of websites captured over a long period of time. Its most famous project is the Wayback Machine, a digital collection of roughly 390 billion pages dating back to 1996. It’s the deepest archive of internet history in existence. Among the IA’s other projects is the Open Library, a virtual library that allows users to freely borrow digital copies of books that are uploaded and archived through the project — both books in the public domain and books under copyright.

As my colleague Constance Grady recently explained, the Internet Archive owns physical copies of all the books it digitizes and claims the right to loan out the digital copies, as long as no more than one digital copy of a book is in circulation at a time. The IA’s right to do so has been endorsed by many librarians and legal experts. But many critics of this approach, especially those within the publishing industry, have long argued that the IA’s Open Library is piracy because it distributes books as image files rather than appropriately licensing the works and compensating authors. Additionally, politicians like North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis, a Republican who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, have attacked the Internet Archive as a way to argue for more stringent copyright laws.

In March, the Internet Archive pushed its already dubious reading of the law even further by temporarily easing its lending restrictions amid the pandemic to allow multiple people to check out the same digital copy of a book at once. The IA dubbed this temporary change the “National Emergency Library.” The IA’s description of what this change meant wasn’t very clear, but in the very last line of a blog post announcing the Emergency Library, it clarified that after the “US national emergency” ended, “The waitlists will be reimplemented thus limiting the number of borrowable copies to those physical books owned.” In other words, while the Emergency Library was underway, IA would loan out more digital files than it actually owned.

By any stretch of the law, that rises to the level of copyright infringement, even though the illegal copies were being shared only temporarily. Whether you view that type of infringement as unethical is a different issue; as the Internet Archive argued, “The idea that this is stealing fundamentally misunderstands the role of libraries in the information ecosystem.”

Publishers predictably found this logic unconvincing. On June 1, Hachette, Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, and other publishers sued the IA, claiming that both the regular Open Library and the Emergency Library are forms of piracy. The IA responded by ending the Emergency Library project on June 16, days after the lawsuit was publicly announced, asking that “the publishers call off their costly assault.” It’s unclear whether the move will actually lead to the suit’s withdrawal. The publishers’ legal representatives referred Vox to the Association of American Publishers, which includes the plaintiffs in the lawsuit. When reached for comment, a representative for the Association shared the group’s statement concerning the suit, which calls the IA “brazen” and “self-serving” and notes that the lawsuit “reflects widespread anger among publishers, authors, and the entire creative community regarding IA’s actions and its response to objections.”

The lawsuit asks the court for two main things: damages for publishers’ copyrighted works, and both a preliminary and permanent injunction of the IA’s digitization and lending processes. That all sounds dire for the Internet Archive’s future. But there seems to be lots of confusion about what the lawsuit’s actual impact on the organization and its various projects will be— and it’s not as bad as previous media reports have indicated.

Rumors of the Internet Archive’s potential demise have been greatly exaggerated

When news of the lawsuit first broke, much of the reporting surrounding it was hyperbolic and alarmist. “A win for the publishers could easily bankrupt the Internet Archive,” reported Ars Technica. “The [suit] puts one of the internet’s largest repositories of knowledge in peril,” reported Vice, which also noted that supporters of the IA’s various preservation projectswere already rushing to try to create backups of the entire archive.

All of this would reasonably give the impression that the publishers’ lawsuit seeks to permanently halt the entire Internet Archive and all of its projects, even the ones that have nothing to do with its book-lending program. What’s more, most of the early reporting about the lawsuit incorrectly claimed that plaintiffs were seeking damages for millions of books in the IA’s giant vault. “If the court finds that Internet Archive ”willfully” infringed copyright,” tech site Decrypt claimed, “the library could be on the hook for up to $150,000 in damages—per each of the 1.4 million titles. (You do the math.)”

Such a sweeping injunction or financial devastation would destroy the IA, and with it the unique and vast records of the Wayback Machine. As a huge repository of internet history, digital record-keeping, and sociocultural trends, the Wayback Machine is essentially irreplaceable — which is why, as news of the lawsuit spread, many of the IA’s supporters were devastated and concerned about the lawsuit potentially destroying its work, especially the WaybackMachine.

But there’s a big problem with all of this — none of it is true.

What is true is that the lawsuit asks for a court injunction against the Internet Archive — but it only asks for a halt to the practice of copying books for loan in the Open Library itself, not the entire IA. And while the IA’s supporters might decry the demise of the library itself — after all, a permanent injunction against digitizing works under copyright would decimate the library, though public domain books would remain available — the lawsuit takes pains to clarify that the publishers aren’t trying to shut down the rest of the Internet Archive.

“Internet Archive provides a number of services not at issue in this action, including its Wayback Machineand digitization of public domain materials,” reads the suit’s complaint.

Then there’s the concern that the lawsuit asks for potentially debilitating financial damages from the archive. If it were true that the publishers claimed $150,000 for each of the millions of books digitized, that could certainly paralyze the entire nonprofit organization.

But in fact, the lawsuit seeks financial damages only for the sharing of 127 books under copyright, including titles like Gone Girl, A Dance with Dragons, and The Catcher in the Rye. If the court awards the plaintiffs the maximum amount provided under the law, the most the Internet Archive would have to pay would be $19 million — essentially equivalent to one year of operating revenue, according to IA tax documents. That’s a huge setback, but for the IA, a tech nonprofit that relies heavily on grants and public donations, it’s not the major death blow it might seem to be.

When asked about its funding reserves, Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle told Vox that “beyond the monetary damages, the publishers are asking for the destruction of 1.4 million books, many of which do not exist in digital form anywhere else. That would be a real tragedy for people who depend on us for access to information.” He declined to comment further on the issue of funding.

The lawsuit might not destroy the IA, but it could hamper the aims of an “open internet”

All that said, a win for the plaintiffs in the lawsuit certainly isn’t ideal.

Much of the confusion and fear that this lawsuit could wipe out the Internet Archive reflects the fragile and ephemeral nature of internet culture, where entire websites can be wiped out overnight if their content isn’t backed up. In the Wayback Machine’s case, the organization provides access to a vital, 10-petabytecollection of internet history. Nothing else is archiving the internet but the Internet Archive itself. If something happens to it, it’s gone for good. And because of that anxiety, the conversation around the lawsuit has left the original copyright debate far behind — even though the lawsuit itself limits its focus to the IA’s Open Library only.

Speaking to Vox’s sister site The Verge, Kahle said the lawsuit was “disappointing” and argued that all of the books in the IA’s library have been uploaded legally:

As a library, the Internet Archive acquires books and lends them, as libraries have always done, Kahle told The Verge. This supports publishing and authors and readers. Publishers suing libraries for lending books — in this case, protected digitized versions, and while schools and libraries are closed — is not in anyone’s interest.

We hope this can be resolved quickly, he continued.

Kahle told Vox that the organization was “confident in our legal position.”

“When nonprofit libraries have been sued in the past for helping their patrons access their collections, courts have ruled that they were engaging in fair use, as in the HathiTrust case,” he said.

While plenty of confusion remains about whether the IA’s Open Library constitutes a legitimate library — and whether its noble purpose justifies some of its more piratical methods — most people agree that its aims are noble. Many of the initiative’s supporters see the IA as a vanguard of the “open internet.” That’s the broad philosophy of free and equal internet access that governs foundational parts of internet culture like open-source coding, Open Access scholarship, the Creative Commons, and the Internet Archive itself.

Kahle touched on this spirit of openness and cooperation, telling Vox, “We need collaboration between libraries, authors, booksellers, and publishers ... We hope for an amicable solution for libraries, authors, booksellers, and publishers because our information health depends on it.” He’s increasingly been joined in his archival efforts by prominent IA supporters. On Monday, the Association of Research Libraries issued a statement asking the publishers to drop the lawsuit.

“For nearly 25 years,” the Association’s statement reads, “the Internet Archive (IA) has been a force for good by capturing the world’s knowledge and providing barrier-free access for everyone, contributing services to higher education and the public, including the Wayback Machine that archives the World Wide Web, as well as a host of other services preserving software, audio files, special collections, and more.”

Because the Internet Archive is a well-established vanguard of open access, the lawsuit could potentially have a larger, chilling effect on internet archival and research practices — even if it fails, and even if that wasn’t the original intent. Let’s hope that the publishing industry can also recognize the Internet Archive as a force for good, before the lawsuit renders it a cautionary tale.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

You Can Now Access 1.4 Million Books for Free Thanks to the Internet Archive

Students, teachers, and readers can now access over 1.4 million books for free as part of the National Emergency Library, a project launched on Tuesday by the Internet Archive to aid remote learning efforts.

Covid-19 has pushed millions of students’ classes online and temporarily shuttered public libraries. The Internet Archive, a nonprofit organization known for creating the Wayback Machine, has previously digitized more than one million books donated by educational institutions and libraries. The books in the National Emergency Library are titles from Open Library, another Internet Archive project, that have had their waitlists removed. Unlike a typical lending library, multiple users can access a single digital copy of a book at the same time.

“Internet Archive’s mission is to provide ‘Universal Access to All Knowledge.’ We believe this is an extraordinary moment in time that requires assistance at a scale that we are able to provide,” reads an FAQ for the project. “Suspending waitlists will put books in the hands of people who need them, supporting emergency remote teaching, research activities, independent scholarship, and intellectual stimulation while universities, schools, training centers, and libraries are closed.”

The National Emergency Library will run until June 30 or the end of the national emergency, whichever comes last. At that date, the waitlist will be reinstated in accordance with fair use, a U.S. doctrine that allows the use of copyrighted materials without permission from the copyright holder. In a blog post announcing the creation of the library, Internet Archive Director of Open Libraries Chris Freeland wrote that the collection was designed to help both students and readers who can’t access their local libraries because of closures or self-isolation.

In contrast to what its name might suggest, the National Emergency Library is free and available to anyone with an internet connection, not just U.S. residents. Textbooks like Introduction to Electrodynamics and Developmental Biology made up some of the most-viewed titles at the time of writing, but were outnumbered by novels and books for pleasure (Things Fall Apart; Call Me by Your Name; Pimp: The Story of My Life).

“The Internet Archive is an invaluable, indispensable asset for researchers, all three of its core features: archived sites, archived files, and books that can be borrowed,” Thomas Rid, professor of strategic studies at Johns Hopkins University, said in an email. “I've borrowed hard-to-get books in the past, and always had to wait for weeks. Now there are more books and no more waiting. This is a fantastic initiative—that hopefully will help get people to spend more time on books and less time on social media.”

According to a University of Washington Libraries blog post, the National Emergency Library has already made a difference in the university’s remote learning efforts.

“Today, I was able to inform 10 instructors that the books they needed were now available, whereas yesterday they were not,” History Librarian Theresa Mudrock told UW Libraries.

Earlier this month, Harvard Copyright Advisor Kyle Courtney authored a blog post arguing that fair use could favor educational use during this pandemic, enabling remote learners to access textbooks and other required readings that are locked in students’ dorm rooms or are otherwise inaccessible.

“Fair use exists exactly for situations like these, where we need to employ the copyright exception to the rule,” Courtney said in an interview. Along with other copyright library experts, Courtney wrote up a statement that the Internet Archive cited as justification for its library in a public statement endorsed by over 100 individuals, libraries, and institutions.

Not everyone agrees that the library is legal or ethical. In 2018, the Authors Guild—the largest professional organization for writers—claimed that the Open Library’s model of digitizing and distributing books without licenses was “in flagrant violation of copyright law.”

Kim Kavin, a freelance writer and editor, is the author of a number of books including Tools of Native Americans: A Kid's Guide to the History & Culture of the First Americans, which was initially listed as a title in the National Emergency Library. Kavin still receives royalties on the book, and in an interview, she compared the actions taken by the Internet Archive to those of Google, which the Authors Guild unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement.

“Everyone in the world is going through a difficult time, and everybody wants to help each other out. But it doesn't mean you get to resort to theft,” she said. She added that had she been asked for permission to use her book, she would have granted it. Tools of Native Americans has since been removed from the National Emergency Library.

"We hope that authors will support our effort to ensure temporary access to their work in this time of crisis," Freeland wrote in the announcement post. "We are empowering authors to explicitly opt in and donate books to the National Emergency Library if we don’t have a copy. We are also making it easy for authors to contact us to take a book out of the library."

It is unlikely that courts will take copyright infringement lawsuits seriously during the national emergency, Courtney said. He pointed to a lawsuit over counterfeit unicorn drawings, which was dismissed by a district judge on March 18.

“This is the idea that people are in this together,” he said. “We're taking advantage of a right that exists, but certainly this has moved conversations about access of technology further in the last three weeks than in the last three years.”

Get a personalized roundup of VICE's best stories in your inbox.

By signing up to the VICE newsletter you agree to receive electronic communications from VICE that may sometimes include advertisements or sponsored content.

What’s New in the Free Internet Calling Archives?

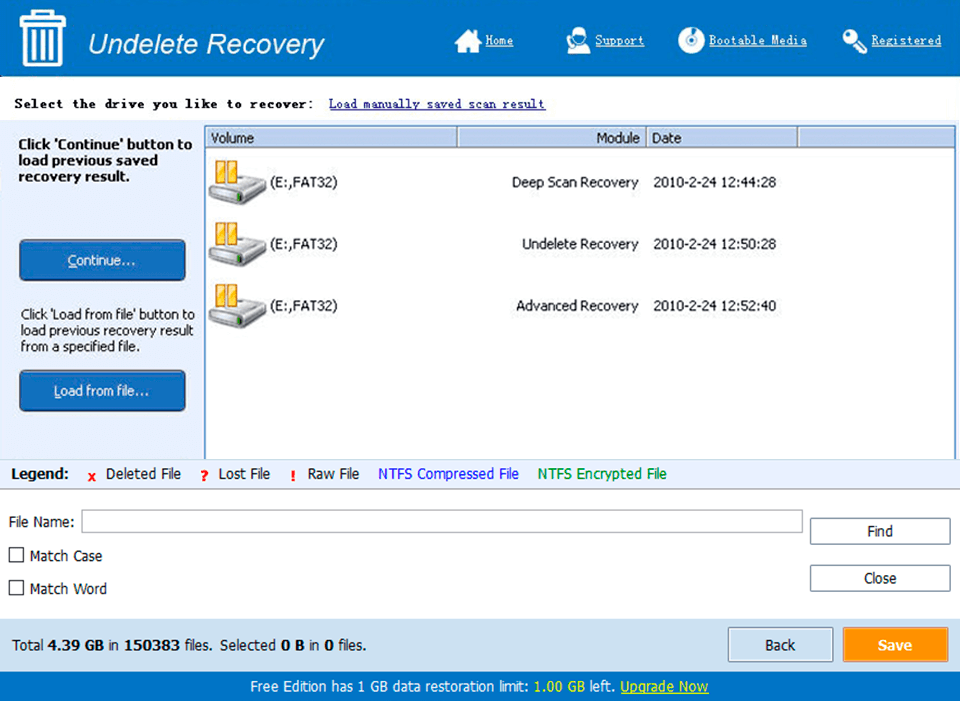

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Free Internet Calling Archives

- First, download the Free Internet Calling Archives

-

You can download its setup from given links: