Best cheap streaming PCs for its price. Archives

best cheap streaming PCs for its price. Archives

Streaming media

Streaming media is multimedia that is constantly received by and presented to an end-user while being delivered by a provider. The verb to stream refers to the process of delivering or obtaining media in this manner.[clarification needed] Streaming refers to the delivery method of the medium, rather than the medium itself. Distinguishing delivery method from the media distributed applies specifically to telecommunications networks, as most of the delivery systems are either inherently streaming (e.g. radio, television, streaming apps) or inherently non-streaming (e.g. books, video cassettes, audio CDs). There are challenges with streaming content on the Internet. For example, users whose Internet connection lacks sufficient bandwidth may experience stops, lags, or slow buffering of the content. And users lacking compatible hardware or software systems may be unable to stream certain content.

Live streaming is the delivery of Internet content in real-time much as live television broadcasts content over the airwaves via a television signal. Live internet streaming requires a form of source media (e.g. a video camera, an audio interface, screen capture software), an encoder to digitize the content, a media publisher, and a content delivery network to distribute and deliver the content. Live streaming does not need to be recorded at the origination point, although it frequently is.

Streaming is an alternative to file downloading, a process in which the end-user obtains the entire file for the content before watching or listening to it. Through streaming, an end-user can use their media player to start playing digital video or digital audio content before the entire file has been transmitted. The term "streaming media" can apply to media other than video and audio, such as live closed captioning, ticker tape, and real-time text, which are all considered "streaming text".

Elevator music was among the earliest popular music available as streaming media; nowadays Internet television is a common form of streamed media. Some popular streaming services include Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, Prime Video, the video sharing website YouTube, and other sites which stream films and television shows; Apple Music and Spotify, which stream music; and the video game live streaming site Twitch.

History[edit]

In the early 1920s, George O. Squier was granted patents for a system for the transmission and distribution of signals over electrical lines,[2] which was the technical basis for what later became Muzak, a technology streaming continuous music to commercial customers without the use of radio. Attempts to display media on computers date back to the earliest days of computing in the mid-20th century. However, little progress was made for several decades, primarily due to the high cost and limited capabilities of computer hardware. From the late 1980s through the 1990s, consumer-grade personal computers became powerful enough to display various media. The primary technical issues related to streaming were having enough CPU power busbandwidth to support the required data rates, creating low-latency interrupt paths in the operating system to prevent buffer underrun, and enabling skip-free streaming of the content. However, computer networks were still limited in the mid-1990s, and audio and video media were usually delivered over non-streaming channels, such as by downloading a digital file from a remote server and then saving it to a local drive on the end user's computer or storing it as a digital file and playing it back from CD-ROMs.

In 1990 the first commercial Ethernet switch was introduced by Kalpana, which enabled the more powerful computer networks that lead to the first streaming video solutions used by schools and corporations. In the mid 1990s the World Wide Web was established, but streaming audio would not be practical until years later.[citation needed]

Multimedia compression[edit]

Practical streaming media was only made possible with advances in data compression, due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed media. Raw digital audio encoded with pulse-code modulation (PCM) requires a bandwidth of 1.4 Mbit/s for uncompressed CD audio, while raw digital video requires a bandwidth of 168 Mbit/s for SD video and over 1000 Mbit/s for FHD video.[3]

The most important compression technique that enabled practical streaming media is the discrete cosine transform (DCT),[4] a form of lossy compression first proposed in 1972 by Nasir Ahmed, who developed the algorithm with T. Natarajan and K. R. Rao at the University of Texas in 1973.[5] The DCT algorithm formed the basis for the first practical video coding format, H.261, in 1988.[6] It was initially used for online video conferencing.[7] It was followed by more popular DCT-based video coding standards, most notably MPEG video formats from 1991 onwards.[4]

The DCT algorithm was adapted into the modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) by J. P. Princen, A. W. Johnson and A. B. Bradley at the University of Surrey in 1987.[8] The MDCT algorithm is fundamental to the MP3 audio format introduced in 1994,[9] and especially the more widely used Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) format introduced in 1999.[10]

Late 1990s to early 2000s[edit]

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, users had increased access to computer networks, especially the Internet. During the early 2000s, users had access to increased network bandwidth, especially in the "last mile". These technological improvements facilitated the streaming of audio and video content to computer users in their homes and workplaces. There was also an increasing use of standard protocols and formats, such as TCP/IP, HTTP, HTML as the Internet became increasingly commercialized, which led to an infusion of investment into the sector.

The band Severe Tire Damage was the first group to perform live on the Internet. On June 24, 1993, the band was playing a gig at Xerox PARC while elsewhere in the building, scientists were discussing new technology (the Mbone) for broadcasting on the Internet using multicasting. As proof of PARC's technology, the band's performance was broadcast and could be seen live in Australia and elsewhere. In a March 2017 interview, band member Russ Haines stated that the band had used approximately "half of the total bandwidth of the internet" to stream the performance, which was a 152-by-76 pixel video, updated eight to twelve times per second, with audio quality that was "at best, a bad telephone connection".[11]

Microsoft Research developed Microsoft TV application compiled under Microsoft Windows Studio Suite and tested in conjunction with Connectix QuickCam. RealNetworks pioneered the broadcast of a baseball game between the New York Yankees and the Seattle Mariners over the Internet in 1995.[12] The first symphonic concert on the Internet—a collaboration between the Seattle Symphony and guest musicians Slash, Matt Cameron, and Barrett Martin—took place at the Paramount Theater in Seattle, Washington, on November 10, 1995.[13]Word Magazine featured the first ever streaming soundtracks on the Internet when it launched in 1995.[citation needed]

Metropolitan Opera Live in HD streams live performances of the Metropolitan Opera. For the 2013–2014 season, ten operas were transmitted via satellite into at least two thousand theaters in sixty-six countries.[14]

Etymology[edit]

The term "streaming" was first used for tape drives manufactured by Data Electronics Inc. that were meant to slowly ramp up and run for the entire track; slower ramp times lowered drive costs. "Streaming" was applied in the early 1990s as a better description for video on demand and later live video on IP networks. It was first done by Starlight Networks for video streaming and Real Networks for audio streaming. Such video had previously been referred to by the misnomer "store and forward video."[15]

Business developments[edit]

The first commercial streaming product appeared in late 1992 and was named StarWorks.[16] StarWorks enabled on-demand MPEG-1 full-motion videos to be randomly accessed on corporate Ethernet networks. Starworks was from Starlight Networks, who also pioneered live video streaming on Ethernet and via Internet Protocol over satellites with Hughes Network Systems.[17] Other early companies who created streaming media technology include RealNetworks (then known as Progressive Networks) and Protocomm both prior to wide spread World Wide Web usage and once the web became popular in the late 90s, streaming video on the internet blossomed from startups such as VDOnet, acquired by RealNetworks, and Precept, acquired by Cisco.

Microsoft developed a media player known as ActiveMovie in 1995 that allowed streaming media and included a proprietary streaming format, which was the precursor to the streaming feature later in Windows Media Player 6.4 in 1999. In June 1999 Apple also introduced a streaming media format in its QuickTime 4 application. It was later also widely adopted on websites along with RealPlayer and Windows Media streaming formats. The competing formats on websites required each user to download the respective applications for streaming and resulted in many users having to have all three applications on their computer for general compatibility.

In 2000 Industryview.com launched its "world's largest streaming video archive" website to help businesses promote themselves.[18] Webcasting became an emerging tool for business marketing and advertising that combined the immersive nature of television with the interactivity of the Web. The ability to collect data and feedback from potential customers caused this technology to gain momentum quickly.[19]

Around 2002, the interest in a single, unified, streaming format and the widespread adoption of Adobe Flash prompted the development of a video streaming format through Flash, which was the format used in Flash-based players on video hosting sites. The first popular video streaming site, YouTube, was founded by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley and Jawed Karim in 2005. It initially used a Flash-based player, which played MPEG-4 AVC video and AAC audio, but now defaults to HTML5 video.[20] Increasing consumer demand for live streaming has prompted YouTube to implement a new live streaming service to users.[21] The company currently also offers a (secured) link returning the available connection speed of the user.[22]

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) revealed through its 2015 earnings report that streaming services were responsible for 34.3 percent of the year's total music industry's revenue, growing 29 percent from the previous year and becoming the largest source of income, pulling in around $2.4 billion.[23][24] US streaming revenue grew 57 percent to $1.6 billion in the first half of 2016 and accounted for almost half of industry sales.[25]

Streaming wars[edit]

The term "streaming wars" was coined to discuss the new era of competition between video streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, HBO Max and Apple TV+.[26]

Use of streaming media by the general public[edit]

These advances in computer networking, combined with powerful home computers and modern operating systems, made streaming media practical and affordable for ordinary citizens. Stand-alone Internet radio devices emerged to offer listeners a no-computer option for listening to audio streams. These audio streaming services have become increasingly popular over recent years, as streaming music hit a record of 118.1 billion streams in 2013.[27] In general, multimedia content has a large volume, so media storage and transmission costs are still significant. To offset this somewhat, media are generally compressed for both storage and streaming. Increasing consumer demand for streaming of high definition (HD) content has led the industry to develop a number of technologies such as WirelessHD or ITU-T G.hn, which are optimized for streaming HD content without forcing the user to install new networking cables. In 1996, digital pioneer Marc Scarpa produced the first large-scale, online, live broadcast in history, the Adam Yauch-led Tibetan Freedom Concert, an event that would define the format of social change broadcasts. Scarpa continued to pioneer in the streaming media world with projects such as Woodstock '99, Townhall with President Clinton, and more recently Covered CA's campaign "Tell a Friend Get Covered" which was live streamed on YouTube.

—Robert Christgau, 2018[28]

A media stream can be streamed either "live" or "on demand". Live streams are generally provided by a means called "true streaming". True streaming sends the information straight to the computer or device without saving the file to a hard disk. On-demand streaming is provided by a means called progressive streaming or progressive download. Progressive streaming saves the file to a hard disk and then is played from that location. On-demand streams are often saved to hard disks and servers for extended amounts of time; while the live streams are only available at one time only (e.g., during the football game).[29] Streaming media is increasingly being coupled with use of social media. For example, sites such as YouTube encourage social interaction in webcasts through features such as live chat, online surveys, user posting of comments online and more. Furthermore, streaming media is increasingly being used for social business and e-learning.[30] Due to the popularity of the streaming medias, many developers have introduced free HD movie streaming apps for the people who use smaller devices such as tablets and smartphones for everyday purposes.

The Horowitz Research State of Pay TV, OTT and SVOD 2017 report said that 70 percent of those viewing content did so through a streaming service, and that 40 percent of TV viewing was done this way, twice the number from five years earlier. Millennials, the report said, streamed 60 percent of content.[31]

Transition from a DVD based to streaming based viewing culture[edit]

One of the movie streaming industry's largest impacts was on the DVD industry, which effectively met its demise with the mass popularization of online content. The rise of media streaming caused the downfall of many DVD rental companies such as Blockbuster. In July 2015, The New York Times published an article about Netflix's DVD services. It stated that Netflix was continuing their DVD services with 5.3 million subscribers, which was a significant drop from the previous year. On the other hand, their streaming services had 65 million members.[32]

The roots of music streaming: Napster[edit]

Music streaming is one of the most popular ways in which consumers interact with streaming media. In the age of digitization, the private consumption of music transformed into a public good largely due to one player in the market: Napster.

Napster, a peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing network where users could upload and download MP3 files freely, broke all music industry conventions when it launched in early 1999 out of Hull, Massachusetts. The platform was developed by Shawn and John Fanning as well as Sean Parker.[33] In an interview from 2009, Shawn Fanning explained that Napster "was something that came to me as a result of seeing a sort of an unmet need and the passion people had for being able to find all this music, particularly a lot of the obscure stuff which wouldn't be something you go to a record store and purchase, so it felt like a problem worth solving."[34]

Not only did this development disrupt the music industry by making songs that previously required payment to acquire freely accessible to any Napster user, it demonstrated the power of P2P networks in turning any digital file into a public, shareable good. For the brief period of time that Napster existed, mp3 files fundamentally changed as a type of good. Songs were no longer financially excludable – barring access to a computer with internet access – and they were not rival, meaning if one person downloaded a song it did not diminish another user from doing the same. Napster, like most other providers of public goods, faced the problem of free riding. Every user benefits when an individual uploads an mp3 file, but there is no requirement or mechanism that forces all users to share their music. Thus, Napster users were incentivized to let others upload music without sharing any of their own files.

This structure revolutionized the consumer's perception of ownership over digital goods – it made music freely replicable. Napster quickly garnered millions of users, growing faster than any other business in history. At the peak of its existence, Napster boasted about 80 million users globally. The site gained so much traffic that many college campuses had to block access to Napster because it created network congestion from so many students sharing music files.[35]

The advent of Napster sparked the creation of numerous other P2P sites including LimeWire (2000), BitTorrent (2001), and the Pirate Bay (2003). The reign of P2P networks was short lived. The first to fall was Napster in 2001. Numerous lawsuits were filed against Napster by various record labels, all of which were subsidiaries of Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, or EMI. In addition to this, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) also filed a lawsuit against Napster on the grounds of unauthorized distribution of copyrighted material, which ultimately led Napster to shutting down in 2001.[35] In an interview with Gary Stiffelman, who represents Eminem, Aerosmith, and TLC, he explained why Napster was a problem for record labels: loss in revenue. In an interview with the New York Times, Stiffelman said, "I’m not an opponent of artists’ music being included in these services, I'm just an opponent of their revenue not being shared."[36]

The fight for intellectual property rights: A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc.[edit]

The lawsuit A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. fundamentally changed the way consumers interact with music streaming. It was argued on 2 October 2000 and was decided on 12 February 2001. The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that a P2P file sharing service could be held liable for contributory and vicarious infringement of copyright, serving as a landmark decision for Intellectual property law.[37]

The first issue that the Court addressed was "fair use," which says that otherwise infringing activities are permissible so long as it is for purposes "such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching [...] scholarship, or research."[38] Judge Beezer, the Judge for this case, noted that Napster claimed that its services fit "three specific alleged fair uses: sampling, where users make temporary copies of a work before purchasing; space-shifting, where users access a sound recording through the Napster system that they already own in audio CD format; and permissive distribution of recordings by both new and established artists."[38] Judge Beezer found that Napster did not fit these criteria, instead enabling their users to repeatedly copy music, which would affect the market value of the copyrighted good.

The second claim by the plaintiffs was that Napster was actively contributing to copyright infringement since it had knowledge of widespread file sharing on their platform. Since Napster took no action to reduce infringement and financially benefited from repeated use, the Court ruled against the P2P site. The court found that "as much as eighty-seven percent of the files available on Napster may be copyrighted and more than seventy percent may be owned or administered by plaintiffs."[38]

The injunction ordered against Napster ended the brief period in which music streaming was a public good – non-rival and non-excludable in nature. Other P2P networks had some success at sharing MP3s, though they all met a similar fate in court. The ruling set the precedent that copyrighted digital content cannot be freely replicated and shared unless given consent by the owner, thereby strengthening the property rights of artists and record labels alike.[37]

Music streaming platforms[edit]

Although music streaming is no longer a freely replicable public good, streaming platforms such as Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music, SoundCloud, and Prime Music have shifted music streaming to a club-type good. While some platforms, most notably Spotify, give customers access to a freemium service that enables the use of limited features for exposure to advertisements, most companies operate under a premium subscription model.[40] Under such circumstances, music streaming is financially excludable, requiring that customers pay a monthly fee for access to a music library, but non-rival, since one customer's use does not impair another's.

Music streaming platforms have grown rapidly in popularity in recent years. Spotify has over 207 million users, as of 1 January 2019, in 78 different countries,[41] Apple Music has about 60 million, and SoundCloud has 175 million.[42] All platforms provide varying degrees of accessibility. Apple Music and Prime Music only offer their services for paid subscribers, whereas Spotify and SoundCloud offer freemium and premium services. Napster, owned by Rhapsody since 2011, has resurfaced as a music streaming platform offering subscription based services to over 4.5 million users as of January 2017.[43] As music streaming providers have proliferated and competition has pushed the price of subscriptions down, music piracy rates have also fallen (see chart to the right).

The music industry's response to music streaming was initially negative. Along with music piracy, streaming services disrupted the market and contributed to the fall in revenue from $14.6 billion in revenue in 1999 to $6.3 billion in 2009 for the U.S. CD's and single-track downloads were not selling because content was freely available on the Internet. The result was that record labels invested more in artists that were "safe" – chart music became more appealing to producers than bands with unique sounds. In 2018, however, music streaming revenue exceeded that of traditional revenue streams (e.g. record sales, album sales, downloads).[44] 2017 alone saw a 41.1% increase in streaming revenue alone and an 8.1% increase in overall revenue.[44] Streaming revenue is one of the largest driving forces behind the growth in the music industry. In an interview, Jonathan Dworkin, a senior vice president of strategy and business development at Universal, said that "we cannot be afraid of perpetual change, because that dynamism is driving growth."[44]

Bandwidth and storage[edit]

A broadband speed of 2 Mbit/s or more is recommended for streaming standard definition video without experiencing buffering or skips, especially live video,[45] for example to a Roku, Apple TV, Google TV or a Sony TV Blu-ray Disc Player. 5 Mbit/s is recommended for High Definition content and 9 Mbit/s for Ultra-High Definition content.[46] Streaming media storage size is calculated from the streaming bandwidth and length of the media using the following formula (for a single user and file): storage size in megabytes is equal to length (in seconds) × bit rate (in bit/s) / (8 × 1024 × 1024). For example, one hour of digital video encoded at 300 kbit/s (this was a typical broadband video in 2005 and it was usually encoded in a 320 × 240 pixels window size) will be: (3,600 s × 300,000 bit/s) / (8×1024×1024) requires around 128 MB of storage.

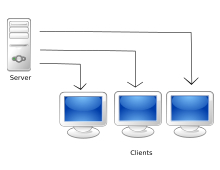

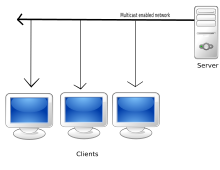

If the file is stored on a server for on-demand streaming and this stream is viewed by 1,000 people at the same time using a Unicast protocol, the requirement is 300 kbit/s × 1,000 = 300,000 kbit/s = 300 Mbit/s of bandwidth. This is equivalent to around 135 GB per hour. Using a multicast protocol the server sends out only a single stream that is common to all users. Therefore, such a stream would only use 300 kbit/s of serving bandwidth. See below for more information on these protocols. The calculation for live streaming is similar. Assuming that the seed at the encoder is 500 kbit/s and if the show lasts for 3 hours with 3,000 viewers, then the calculation is number of MBs transferred = encoder speed (in bit/s) × number of seconds × number of viewers / (8 × 1024 × 1024). The results of this calculation are as follows: number of MBs transferred = 500 x 1024 (bit/s) × 3 × 3,600 ( = 3 hours) × 3,000 (number of viewers) / (8 × 1024 × 1024) = 1,977,539 MB.[dubious – discuss]

Protocols[edit]

The audio stream is compressed to make the file size smaller using an audio coding format such as MP3, Vorbis, AAC or Opus. The video stream is compressed using a video coding format to make the file size smaller. Video coding formats include H.264, HEVC, VP8 or VP9. Encoded audio and video streams are assembled in a container "bitstream" such as MP4, FLV, WebM, ASF or ISMA. The bitstream is delivered from a streaming server to a streaming client (e.g., the computer user with their Internet-connected laptop) using a transport protocol, such as Adobe's RTMP or RTP. In the 2010s, technologies such as Apple's HLS, Microsoft's Smooth Streaming, Adobe's HDS and non-proprietary formats such as MPEG-DASH have emerged to enable adaptive bitrate streaming over HTTP as an alternative to using proprietary transport protocols. Often, a streaming transport protocol is used to send video from an event venue to a "cloud" transcoding service and CDN, which then uses HTTP-based transport protocols to distribute the video to individual homes and users.[47] The streaming client (the end user) may interact with the streaming server using a control protocol, such as MMS or RTSP.

The quality of the interaction between servers and users is based on the workload of the streaming service; as more users attempt to access a service, the more quality is affected unless there is enough bandwidth or the host is using enough proxy networks.[48] Deploying clusters of streaming servers is one such method where there are regional servers spread across the network, managed by a singular, central server containing copies of all the media files as well as the IP addresses of the regional servers. This central server then uses load balancing and scheduling algorithms to redirect users to nearby regional servers capable of accommodating them. This approach also allows the central server to provide streaming data to both users as well as regional servers using FFMpeg libraries if required, thus demanding the central server to have powerful data-processing and immense storage capabilities. In return, workloads on the streaming backbone network are balanced and alleviated, allowing for optimal streaming quality.[49]

Protocol challenges[edit]

Designing a network protocol to support streaming media raises many problems. Datagram protocols, such as the User Datagram Protocol (UDP), send the media stream as a series of small packets. This is simple and efficient; however, there is no mechanism within the protocol to guarantee delivery. It is up to the receiving application to detect loss or corruption and recover data using error correction techniques. If data is lost, the stream may suffer a dropout. The Real-time Streaming Protocol (RTSP), Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) and the Real-time Transport Control Protocol (RTCP) were specifically designed to stream media over networks. RTSP runs over a variety of transport protocols, while the latter two are built on top of UDP.

Another approach that seems to incorporate both the advantages of using a standard web protocol and the ability to be used for streaming even live content is adaptive bitrate streaming. HTTP adaptive bitrate streaming is based on HTTP progressive download, but contrary to the previous approach, here the files are very small, so that they can be compared to the streaming of packets, much like the case of using RTSP and RTP.[50] Reliable protocols, such as the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), guarantee correct delivery of each bit in the media stream. However, they accomplish this with a system of timeouts and retries, which makes them more complex to implement. It also means that when there is data loss on the network, the media stream stalls while the protocol handlers detect the loss and retransmit the missing data. Clients can minimize this effect by buffering data for display. While delay due to buffering is acceptable in video on demand scenarios, users of interactive applications such as video conferencing will experience a loss of fidelity if the delay caused by buffering exceeds 200 ms.[51]

Unicast protocols send a separate copy of the media stream from the server to each recipient. Unicast is the norm for most Internet connections, but does not scale well when many users want to view the same television program concurrently. Multicast protocols were developed to reduce the server/network loads resulting from duplicate data streams that occur when many recipients receive unicast content streams independently. These protocols send a single stream from the source to a group of recipients. Depending on the network infrastructure and type, multicast transmission may or may not be feasible. One potential disadvantage of multicasting is the loss of video on demand functionality. Continuous streaming of radio or television material usually precludes the recipient's ability to control playback. However, this problem can be mitigated by elements such as caching servers, digital set-top boxes, and buffered media players.

IP Multicast provides a means to send a single media stream to a group of recipients on a computer network. A multicast protocol, usually Internet Group Management Protocol, is used to manage delivery of multicast streams to the groups of recipients on a LAN. One of the challenges in deploying IP multicast is that routers and firewalls between LANs must allow the passage of packets destined to multicast groups. If the organization that is serving the content has control over the network between server and recipients (i.e., educational, government, and corporate intranets), then routing protocols such as Protocol Independent Multicast can be used to deliver stream content to multiple Local Area Network segments. As in mass delivery of content, multicast protocols need much less energy and other resources, widespread introduction of reliable multicast (broadcast-like) protocols and their preferential use, wherever possible, is a significant ecological and economic challenge.[citation needed]Peer-to-peer (P2P) protocols arrange for prerecorded streams to be sent between computers. This prevents the server and its network connections from becoming a bottleneck. However, it raises technical, performance, security, quality, and business issues.

Applications and marketing[edit]

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it.(December 2016) |

Useful – and typical – applications of the "streaming" concept are, for example, long video lectures performed "online" on the Internet.[52] An advantage of this presentation is that these lectures can be very long, although they can always be interrupted or repeated at arbitrary places. There are also new marketing concepts. For example, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra sells Internet live streams of whole concerts, instead of several CDs or similar fixed media, by their so-called "Digital Concert Hall"[53] using YouTube for "trailing" purposes only. These "online concerts" are also spread over a lot of different places – cinemas – at various places on the globe. A similar concept is used by the Metropolitan Opera in New York. There also is a livestream from the International Space Station.[54][55]

Recording[edit]

Media that is live streamed can be recorded through certain media players such as VLC player, or through the use of a screen recorder. Live-streaming platforms such as Twitch may also incorporate a video on demand system that allows automatic recording of live broadcasts so that they can be watched later.[56] The popular site, YouTube also has recordings of live broadcasts, including television shows aired on major networks. These streams have the potential to be recorded by anyone who has access to them, whether legally or otherwise.[57]

Copyright[edit]

Streaming copyrighted content can involve making infringing copies of the works in question. The recording and distribution of streamed content is also an issue for many companies that rely on revenue based on views or attendance.[58]

Greenhouse gas emissions[edit]

The net greenhouse gas emissions from streaming music have been estimated at between 200 and 350 million kilograms per year in the United States, according to a 2019 study.[59] This is an increase from emissions in the pre-digital music period, which were estimated at "140 million kilograms in 1977, 136 million kilograms in 1988, and 157 million in 2000."[60]

There are several ways to decrease greenhouse gas emissions associated with streaming music, including efforts to make data centerscarbon neutral, by converting to electricity produced from renewable sources. On an individual level, purchase of a physical CD may be more environmentally friendly if it is to be played more than 27 times.[61] Another option for reducing energy use can be downloading the music for offline listening, to reduce the need for streaming over distance.[61] The Spotify service has a built-in local cache to reduce the necessity of repeating song streams.[62]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"Schou FishCam". 16 December 2014. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014.

- ^"US Patent 1,641,608". Google Patents.

- ^Lee, Jack (2005). Scalable Continuous Media Streaming Systems: Architecture, Design, Analysis and Implementation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 25. ISBN .

- ^ abCe, Zhu (2010). Streaming Media Architectures, Techniques, and Applications: Recent Advances: Recent Advances. IGI Global. p. 26. ISBN .

- ^Nasir Ahmed (1991). "How I Came Up With the Discrete Cosine Transform". Digital Signal Processing. 1 (1): 4–5. doi:10.1016/1051-2004(91)90086-Z.

- ^Ghanbari, Mohammed (2003). Standard Codecs: Image Compression to Advanced Video Coding. Institution of Engineering and Technology. pp. 1–2. ISBN .

- ^Huang, Hsiang-Cheh; Fang, Wai-Chi (2007). Intelligent Multimedia Data Hiding: New Directions. Springer. p. 41. ISBN .

- ^Princen, J.; Johnson, A.; Bradley, A. (1987). "Subband/Transform coding using filter bank designs based on time domain aliasing cancellation". ICASSP '87. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. 12: 2161–2164. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.1987.1169405.

- ^Guckert, John (Spring 2012). "The Use of FFT and MDCT in MP3 Audio Compression"(PDF). University of Utah. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^Brandenburg, Karlheinz (1999). "MP3 and AAC Explained"(PDF). Archived(PDF) from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^"History of the Internet Pt. 1 – The First Live Stream". From YouTube.com. Internet Archive – Stream Division. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^"RealNetworks Inc". Funding Universe. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^"Cyberian Rhapsody". Billboard. United States: Lynne Segall. 17 February 1996.

- ^Pamela McClintock, "Met Opera Standoff Threatens $60 Million Theater Business", The Hollywood Reporter (online), 7 August 2014 on hollywoodreporter.com

- ^Gelman, A.D.; Halfin, S.; Willinger, W. (1991). "On buffer requirements for store-and-forward video on demand service circuits". IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference GLOBECOM '91: Countdown to the New Millennium. Conference Record. IEEE. pp. 976–980. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.1991.188525. ISBN .

The Best $750 Budget Gaming PC Build - September 2020

- By Ari Altman

- Published August 31, 2020

- Updated August 31, 2020

Looking to build a budget gaming PC that's anything but "cheap?" Then our $750 Budget Gaming PC Build is the one for you! While it doesn't have all the bells and whistles you'll find in higher-priced systems, like liquid cooling, tons of RAM, or fancy RGB lighting, for pure gaming purposes, this build offers the best bang for the buck you'll find. That means fantastic performance in all of today's latest games without breaking the bank!

For September 2020, the $750 Budget Gaming PC Build features the awesome Intel Core i3-10100, the first budget-friendly Core i3 processor to offer gaming performance that matches the big guys. That's thanks to its four cores and 8 threads, which no previous desktop Core i3 has offered. It also has a much higher clockspeed that competing AMD processors, which puts it ahead for games. With that said, we still show AMD some love, recommending its Radeon RX 580 8GB, which after another major price cut is the clear choice for the $750 Budget Gaming PC Build. That's in part due to its 8GB of VRAM, which is twice what Nvidia will give you at this pricepoint. Simply put, 4GB of VRAM is not enough for modern games! In terms of storage, the $750 Budget Gaming PC Build sports a 512GB solid-state drive. Most other "budget gaming PCs" you'll find on the 'Net still use hard drives, which is a sure sign that whoever's suggesting them has no idea what they're talking about! An SSD ensures that the $750 Budget Gaming PC Build doesn't feel budget at all - it's going to launch your games and everything else in a flash! Another important upgrade the $750 Budget Gaming PC Build has over others on the 'net is 16GB of RAM - skimping by going with 8GB would cause your gaming PC to hit the page file in the latest games, leading to massive hitching. The $750 Budget Gaming PC Build is powered by a high-output power supply and wrapped up in a stylish, compact Cooler Master case. If you'd like to accessorize the $750 Budget Gaming PC Build, just check out our recommendations for budget-friendly PC peripherals at the end of this guide, including our favorite low-cost 144Hz monitor and a great budget gaming mouse.

We update this build monthly, as prices and components in this market segment change frequently, and a few dollars here or there could buy you (or cost you) a lot of speed! To see past part selections, flip over to the Budget Gaming PC Build Archive. Throughout this guide, we provide links to Amazon, Amazon Canada, Amazon UK, and Amazon Germany, and our US links will auto-convert for our readers in Spain, France, and Italy. Your use of these links is the only thing that keeps this site on the 'net!

The $750 Budget Gaming PC Build - September 2020

The Pre-Built Option

The Budget Gaming PC:

Acer Nitro 50 N50-600-UR1H

Don't want to build your own? Then pick up a powerhouse of a gaming PC from Acer and score a true deal! This tower comes packing an Intel Core i5-9400F six-core CPU, a GeForce GTX 1650 4GB video card, 8GB of DDR4 RAM, and a 512GB solid-state drive, plus built-in WiFi. Wow!

The Guru's Tip:

This PC is also available with an upgraded GTX 1660 Ti 6GB video card. If you can swing it, that's a great upgrade for the money!

The Build-Your-Own Option

CPU:

Intel Core i3-10100

Under pressure from AMD, Intel has come out with a budget gaming winner, the Core i3-10100. With four cores and 8 threads, along with a boost speed well above 4GHz, it will rip through just about any game, and yes, it's faster than anything AMD has to offer anywhere near this price range.

The Guru's Tip:

Note that this CPU comes with a cooler in the box, and you'll be using it in this build.

Motherboard:

Gigabyte B460M DS3H

This board is the perfect choice for a low-cost build. With three PCIe slots, six USB ports, four RAM slots, and six SATA ports, it gives the system room to grow. Plus it has a PCIe M.2 slot, which you'll be taking advantage of with this build's SSD!

The Guru's Tip:

Make sure not to accidentally buy any of the following boards: B360 (that's old Intel, not compatible!), B450 (that's AMD!), or B550 (that's AMD too!).

Video Card:

MSI Radeon RX 580 8GB Armor

There's a huge battle being waged in the $150-$200 GPU segment, and while AMD and Nvidia have released a bunch of new cards in recent months, none of them can actually beat the proven RX 580 8GB, the fastest card under $200, period. It easily beats Nvidia's similarly-priced GTX 1650 Super 4GB, and has double the VRAM too, meaning it's much more future-proof!

The Guru's Tip:

To get the most out of this card, we suggest you pair it with a frame-syncing monitor, like the one listed at the end of this guide!

Memory:

Patriot 2x8GB Viper Elite DDR4-2666 Grey

This kit offers a 2666MHz speed rating, the fastest supported by the Core i3-10100 chip. And with 16GB of total capacity, it will ensure all your latest games run smoothly!

The Guru's Tip:

We no longer recommend 8GB of RAM for a gaming system, even a budget gaming PC build. There's just too much chance that modern games will use the entire amount, slowing the system down to a crawl.

Solid-State Drive:

Silicon Power 512GB NVMe

Simply put, any PC you build today must have an SSD. If you see build guides suggesting you set up your budget gaming PC build with a hard drive as your system drive, they're giving you bad advice.

The Guru's Tip:

Yes, you trade a little capacity going with an SSD, but consider that this drive is about 10x faster than any hard drive, and you'll understand that the tradeoff is worth it. So load up Windows and a bunch of your favorite games, and prepare to be blown away!

Case:

Cooler Master MasterBox Q300L

The Q300L offers plenty of features plus a sleek style at a bargain price. With a vented front panel, a 120mm exhuast fan, and a transparent side panel, you get performance and looks well beyond the price paid!

The Guru's Tip:

It's possible you'll need to backorder this case - most are actually sold out and totally unavailable!

Power Supply:

Silverstone ET550-B

This model is an awesome pick for the Budget Gaming PC Build. With 550W of power and dual PCIe power cables, it can easily handle this system, and will even power up any high-end GPU upgrade you want to add down the line!

The Guru's Tip:

Due to current worldwide supply chain issues, we are making daily substitutions to our PSU recommendation to help you get your hands on one fastest. You're actually lucky if you can even backorder one - most aren't even for sale at this point.

Operating System:

Microsoft Windows 10 Flash Drive

Windows 10 is so much better than Windows 8.1, it makes us wonder whether Microsoft even tested Win8 in the first place. Windows 10 is easy to use right out of the box, and has a lot of refinements under the hood as well.

The Guru's Tip:

Windows 10 on USB recently sold out at Amazon, but as of our most recent update, it's back in stock.

Optional Components

Wireless Card:

TP-Link Archer T4E AC1200

Add high-speed wireless networking to your gaming PC with this awesome expansion card, which packs in dual-stream 802.11ac networking.

The Guru's Tip:

This will fit into the one free PCIe slot available once the video card is installed.

Hard Drive:

Seagate Barracuda 2TB

If you need more space for games and want the most cost effective bulk storage you can get, you want the Barracuda 7200RPM hard drive. It simply can't be beat in terms of value.

The Guru's Tip:

Remember, you do not want to use this for your OS installation, which should be on an SSD. A hard drive should only be used as secondary storage capacity.

The Budget Gaming Keyboard:

Logitech G213 Gaming Keyboard @Newegg

Logitech is driving a bargain that none of the generics you'll find on the market can even touch: a legitimate gaming keyboard with sweet RGB lighting that can be controlled via Logitech's GHub software.

The Guru's Tip:

There are a lot of knock-off keyboards on the market selling for around the same price - our advice: avoid them!

The Mainstream Gaming Mouse:

Logitech G502 Hero

Featuring a 16,000dpi sensor, RGB lighting, and a great ergonomic grip, this mouse easily beats all the knock-off gaming mice that sell for the same price. Avoid them at all costs!

The Guru's Tip:

This has been the world's top-selling mouse since 2014!

The 24-inch 144Hz Gaming Monitor:

Sceptre E248B-FPT168

If you want to pick up a true "gaming" monitor, you want something with a high refresh rate. And this is the very best value out there in high-refresh-rate monitors. It features a 24" 1920x1080 IPS panel capable of displaying images at up to 165Hz over DisplayPort or 144Hz over HDMI 2.0, which makes it infinitely smoother than a standard 60Hz monitor that costs just a bit less. And thanks to its FreeSync technology, it will run with zero lag or screen-tearing.

The Guru's Tip:

This monitor is only available in the US as of our latest update, so we've linked to a different model for other regions.

The Bargain Gaming Headset:

HyperX Cloud Stinger

Assuming you actually want to hear the bullets whizzing by you in your games, you're going to need a great audio source, and there's no better budget gaming headset on the market than the Stinger from HyperX! With 50mm drivers and a comfortable fit, it's the real deal, where all the other headsets in its price range are just pretending.

The Guru's Tip:

Read our full review right here!

How to build a custom PC for gaming, editing or coding

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article included a video guide detailing similar steps on how to build a PC. Unfortunately, that video included a number of errors in the build process, and as a result we have removed it from this article. We have also updated this article to improve the order of the steps in the process.

Building your own Windows desktop has many advantages over buying one pre-built. You can get parts suited exactly to your needs, which can also potentially lead to cost savings. You can get a customized look that’s unique to your PC. You don’t have to deal with things like bloatware or annoying pre-installs. It’s also a learning experience: by building your own computer, you’ll have a better grasp on how it all works.

You don’t need to spend thousands of dollars to build a great desktop, though the more you do spend up front, the longer your PC will still be current. The beauty of building your own Windows desktop is you can price and build exactly for your needs. For example, if you’re a video editor, a lot of your build cost should be going toward extra RAM (more temporary storage and faster edits) and hard drive space to store your projects (an extra SSD, for example).

In our example build, we wanted a PC that would excel at playing high-end games now and for the next few years. For that need, we had to prioritize a great GPU (graphics card) so we could play popular titles at their highest graphical settings. And eventually, to upgrade to an RTX 2080, to support future titles in HD or 4K that use ray tracing. The budget we set for this was $2,000, all-in, including a license for Windows 10Home. That’s not cheap, but it’s enough to ensure that this PC will still be capable a few years down the road.

To make this process easier, I used PCPartPicker to organize the list of parts I’d use, ensure there were no compatibility issues between them, and make sure I’m within my budget. It’s a great way to make sure that everything you’re buying works together before you’ve got it all laid out on your workbench.

Precautions

Before we get started, there are a couple of things you should be wary of. First off, you are handling parts that draw several hundred watts of the power, so don’t ever touch the parts with the system powered on.

It’s smart to wear an anti-static bracelet (or ground yourself by touching a metal object / items bound to the floor) so that you don’t give your PC parts ESD (electrostatic discharge) and damage them in the process.

For your work surface, use a plastic or wooden table for the build process, or any other surface with a working mat that has anti-static properties. Additionally, have plenty of patience and two different sizes of Phillips screwdriver.

If you have to make a quick change — like adjust a graphics card or plug in an extra cable — make sure to first unplug the power cable from the wall outlet and power cycle the desktop by pressing the power button to get any remaining electricity out of the system.

In regards to the parts you’re using, always make sure the socket of the processor and motherboard combo you bought match (in my case, an LGA 1151 processor on an LGA 1151 motherboard). The socket type goes for the CPU cooler you’re using, too. (This is where PCPartsPicker comes in handy — it will tell you if you try to buy a processor that doesn’t fit on your selected motherboard and vice versa.)

The buying process

So what parts do you need for your build? Well, there are the essentials: RAM, a case, graphics, processor, cooler, thermal paste, operating system, motherboard, and finally, the power supply. Which manufacturer you use for each part is entirely up to you. However, there are some things you should keep in mind.

First, determine what your computer will be for. If it’s a gaming desktop, pay close attention to your RAM, CPU, and GPU trio — they’ll need to be the highest-end parts in the system. If you’re a video editor, drop costs on the graphics and spend more on storage and RAM, for example.

If you’re planning to not spend too much on parts now (or don’t know which to prioritize), but want to make easy upgrades in the future, pick a power supply with enough wattage to support higher-end parts (they require more power). An easy way of doing this: use PCPartPicker to estimate the power needed on your behalf, or you can look up the power requirements of each individual part.

In our build, the parts we’ve selected are currently using an estimated 374 watts, but by having an 850 watt PSU, I can add two graphics cards or a single, higher-end card without worrying about if I have enough power. Of course, if you’re on a tighter budget and decide you won’t be using any high-end parts, pick a power supply that’s just enough for the parts you have right now.

Once you’ve decided the “what for,” it’s time to determine what sort of desktop it will be. That means first deciding on a case. Obviously, the case determines the footprint of your completed build, but it also plays a big part in which parts you’ll be able to use inside of it.

There are three popular case types: mini-ITX (the smallest, most restrictions), mATX (compact, but easy to work with), and full ATX (typical heavy desktop tower). Each of those has their pros and cons, but most people will probably be fine with an mATX size case. The case size you choose will dictate your motherboard options: the Corsair 280X case I used for this build is an mATX case, which means I have to buy an mATX motherboard to fit inside of it.

My ATX power supply is produced by Corsair as well, so it’s designed to fit in this case, but you should always check your case specification and learn what motherboard and power supply size it can house best.

The rest of the components you’ll need fall into line after the motherboard: processor, cooling, RAM, GPU, and thermal paste. You’ll want to make sure that your motherboard has things like built-in Wi-Fi, Ethernet, sound, and Bluetooth, so you don’t have to worry about adding those components separately. Fortunately, it’s not hard to find a motherboard that has all of those things onboard already.

The build process

The first part of the build should be orderly laying out everything you’ve purchased: the processor, RAM, graphics, all the screws, cable ties, fan screens... everything. This way you won’t stop building midway and go looking for that elusive motherboard screw.

DIY PC build specs

- Processor: Intel Core i7-8700K 3.7GHz 6-Core

- CPU Cooler: Corsair H115i PRO

- Motherboard: Asus ROG STRIX Z370-G Micro ATX LGA1151

- RAM: Corsair Vengeance LED 16GB (2 x 8GB) DDR4-3333

- Storage: Kingston UV500 480GB M.2-2280 SSD

- GPU: PNY GeForce GTX 1080 8GB XLR8 Video Card

- Case: Corsair Crystal 280X MicroATX

- PSU: Corsair 850W 80+ Gold Semi-Modular ATX

- Thermal Paste: ARCTIC MX4

- OS: Windows 10 Home 64-Bit

Total Cost: $1,948.94

From there, where you start is up to you, but I prefer to start by mounting the power supply. By installing the PSU first, I can single out all the required wires, and make space for them. Generally, it’s a safe step that is difficult to mess up. Also, this is personal preference, but in all of my prior builds, I decided to install every major part in the desktop before I start wiring them to each other and to the power supply.

Next, mount that motherboard. Depending on your socket type (AMD or Intel), you may need to install a back brace for the motherboard, so do that first. Afterward, screwing down a handful of small screws, aligned with motherboard and the case, should keep this integral part of your DIY PC build in place.

The rest of the build is more about plug-and-play. For starters, installing RAM is a piece of cake: just align your gold connectors with the center of the slot, slowly pushing down till you hear a click. It is important to make sure you’re putting the RAM in the correct slots, however. If you have dual-channel RAM, which you most likely do, it needs to be installed in the dual-channels slots on the motherboard.

Installing your GPU is also a straightforward process, except you have to open the expansion bracket at the back of your case (it’s usually held down by screws). From there, align your card’s gold connector with the motherboard’s slot and the back of the case, pressing down firmly until you hear a click.

On the flipside, installing your processor is probably the most intense part of the build. CPUs are very delicate (and expensive), so you should only really place it down in the processor socket once. Open the socket using the latch, then align the arrow that appears on your chip with the corresponding arrow on the motherboard. Gently pull the latch down, ensuring the processorhasn’t moved out of place, at all.

At this point, you should install the radiator and fans that will cool off your desktop PC. I decided to mount the CPU cooler on top of the case, with two fans providing additional cooling on the front of the case. Again, this is all according to your own budget and specifications. However, it’s best in a micro ATX tower like this one to have two fans in your radiator and another two to cool the rest of the case.

Liquid cooling is entirely possible in a DIY build, but it’s more expensive than installing fans and only necessary for overclocking or intensive processing.

With your fans in place, you can finally proceed to applying thermal paste to the top of your processor. You should apply a paper-thin layer of paste spread evenly on top of the CPU. From there, screw in the remaining screws to secure your cooler on top of the processor.

- Photo by Amelia Holowaty Krales / The Verge

So now that all your PC parts are installed and fit together inside the case, it’s time to wire everything. This is a tedious and tricky process that involves knowing exactly which cables to use (your motherboard manual does a good job of explaining this).

In this build, I’m using numerous connectors for the front panel’s ports, audio inputs, and power button. This also includes power cables to the graphics card, CPU, motherboard, fan controller, individual fans, pump, and Wi-Fi antennae.

The major cables (PCI-E, 24-pin, CPU, etc.) are usually labeled and not alike at the ends visually, so there shouldn’t be too much cause for confusion there. Where you might run into some hurdles is connecting the tiny three to four pin cables that correspond with your case’s ports and fans. If you can’t tell which pins these cables should go to, your motherboard’s manual usually has a map of every port / connection on the board. From there, it should be simple.

So now you’ve nearly reached the end of your PC build. At this point, you want to make sure all your wires are installed, connections to the motherboard are secure, power supply switch is turned on and plugged into a wall outlet. Next, connect your newly built desktop to a monitor, mouse, and keyboard setup.

Finally, hit the power button. You should see a screen that bears the brand name of your motherboard. This indicates a successful Power-On Self Test (or POST, for short).

Now, plug in a USB stick with Windows 10 installation files (which you can learn about here), restart the PC, and select your boot device as the USB drive you just inserted. Follow the on-screen prompt, enter your Windows license key, and finally reach the desktop.

However, you’re still not done yet! Download and install the relevant motherboard, GPU, cooling, lighting, and networking drivers or apps that will ensure everything is running as intended. This is non-negotiable and required if you actually want your new desktop PC to run at its peak.

Congrats, you’ve just built and configured a Windows desktop.

Future upgrades

Part of the appeal for building your own desktop are the future upgrades. In this PC, there’s an 8GB Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 supplied by PNY, but if you’re sticking with current generation graphics cards and want something with a bit more oomph, buy an 11GB GeForce 1080Ti Turbo card by ASUS; it should get you the extra frames needed on an ultrawide monitor, for example.

Meanwhile, 4K gameplay and ray tracing is out of the question for current Nvidia GeForce graphics cards, but thanks to the headroom afforded to me by the 850 watt power supply, I’ll be able to just swap out these cards for an RTX 2080 once those are available.

The versatility of swapping out current parts for new(er) ones — like a faster SSD, RGB backlit fans, more Corsair RAM — is one of the best aspects of PC building. And honestly, it’s just a lot of fun.

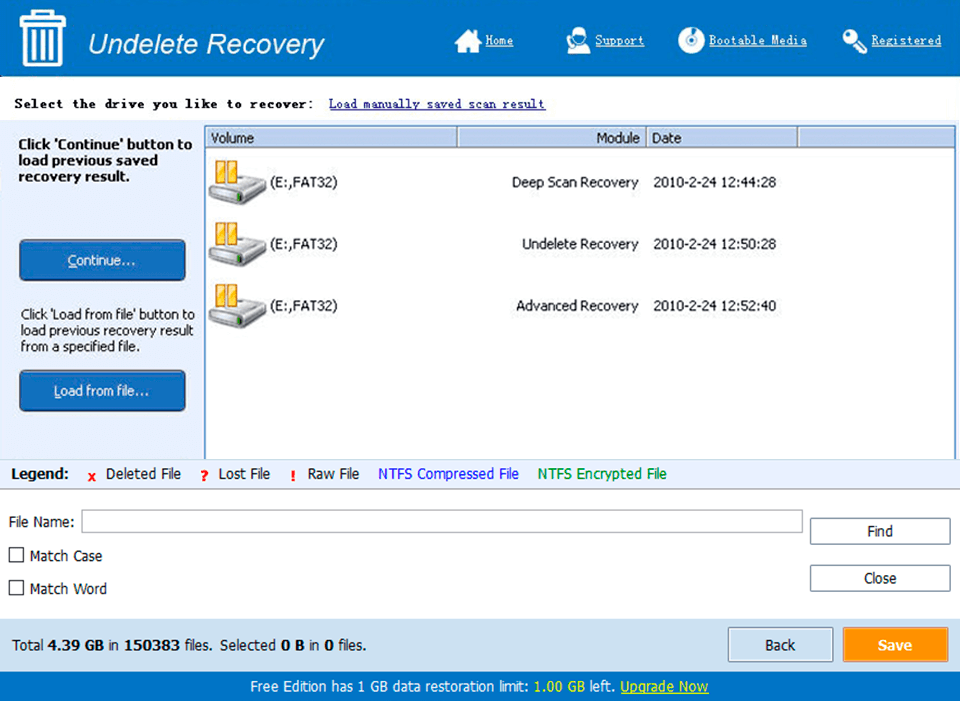

What’s New in the best cheap streaming PCs for its price. Archives?

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Best cheap streaming PCs for its price. Archives

- First, download the Best cheap streaming PCs for its price. Archives

-

You can download its setup from given links: