Learning combat in For Honor Archives

learning combat in For Honor Archives

For Honor

A horn sounds in the distance, signaling that our army is at its breaking point. I look down at the grassy field from the relative safety of a crumbling wall. One of my comrades is clashing with a knight, doing his best to block the unrelenting swings of his opponent’s morning star. Two of the knight’s allies come, and it’s three against one. I could run down and help, but even then we’d be outnumbered. Instead, I call in a volley of arrows. The projectiles rain down on our enemies, slaughtering them in seconds. Our ragged forces regroup, and we manage to narrowly pull a victory from what seemed like an inevitable loss. At its best, For Honor lets you live out the fantasies you had as a kid, where every stick was a blade and your backyard was a roiling battleground waiting for your swordsmanship to save the day.

For Honor’s setup is either supremely strange or just plain stupid: The best warriors from three different factions – knights, samurai, and vikings – have been pulled into a realm of war, where they continue to fight for 1,000 years. A campaign attempts to make sense of it all, but ultimately it’s an excuse to get a dozen heroes from various cultures together so they can fight to the death. I couldn’t say with any confidence what exactly is ultimately going on in For Honor’s story, aside from the fact that these guys like to fight.

The combat system is easily the highlight, working as a solid foundation for the rest of the diverse modes. It’s a 3D action/fighting hybrid that slashes its own unique path; the warriors have a variety of different weapons, including poison-tipped spears, battleaxes, and katana, but the fundamentals are the same regardless. Your hero can hold his or her weapon in three directional positions, for either attacking or defending. Switching positions is as simple as locking onto your opponent and moving the right analog stick. Add in feints, parries, block-breakers, and unique movesets, and you have a robust melee toolset.

Battles are methodical and thoughtful. Button-mashers quickly run out of stamina, leaving them vulnerable. A refreshing amount of tension comes at the start of battle, and I loved how often the initial moments of contact would consist of me and my opponent circling one another while switching stances, looking for weaknesses and openings. This kind of psychological engagement is at its best in one-on-one duels or two-on-two brawls, where you’re able to focus your attention and get into your opponent’s head – and hopefully remove it.

Things are more frantic in the Dominion mode, where two teams of four earn points by taking and controlling three points on a large map. Double- or triple-teaming the enemy is commonplace there, but For Honor helps even the odds by making it easier to block attacks coming from several directions and also allowing the outnumbered party to quickly fill a revenge meter. Once activated, it can knock attackers down, providing a chance for retribution or escape. Being able to endure such an onslaught, and even overcome it, is intensely satisfying, and one of my favorite things about For Honor.

Even though characters share the basics, don’t expect to jump between them at ease. You need to learn each hero’s range, chain attacks, and various feats if you want to be effective. As silly as the story is, it does a great job letting you try out several of the different classes to see which ones best fit your playstyle. Early on, I gravitated toward the Viking Warchief, but I found his limited stamina to be a problem (even after equipping items that boosted the stat). Once I started playing as the Samurai Kensei, however, I flourished.

As you play more with the characters, you level them up and get better gear. Thankfully, their associated stat boosts don’t matter in the skill-based duels and brawls, but they can make a difference in some of the other modes. You can earn them via random drops or buy blind bundles of gear using the in-game currency, steel, which is earned in matches and daily missions. Earning steel through matches alone is a slow process, with a typical Dominion battle earning about 40. You need 500 steel to open the best bundles, and even more to purchase additional taunts, costumes, or other cosmetic items. Most of this is purely optional, but it’s a little gross to see more than $200 of microtransaction content laid out the first week of the game’s release – including the ability to fast-track your way to character feats that would take dozens of hours to otherwise unlock, or to purchase a special account status that earns you additional loot and XP.

For Honor’s battles can be great, but you also have to contend with the online infrastructure. In its current state, I experienced frequent disconnects and other networking issues. Players would vanish before my eyes, and the action would stutter as it replaced the missing person with an admittedly competent bot. That this happens at all is disconcerting, and more so when the screen hitches as an enemy sword is swinging at your face. Sometimes these disconnects also shatter online parties, requiring you to send another wave of invites. Ubisoft has big plans for For Honor in the months ahead, with a faction-based metagame, evolving stages, and additional characters to join the war. Hopefully, addressing these technical issues is even higher on the list of priorities, because they undermine an otherwise memorable experience.

When everything lines up, For Honor is a brutal and rewarding game that makes you feel like an unstoppable warrior. Sure, sometimes you get kicked off a bridge (again) or your head gets lopped off, but those failures make your battlefield successes even sweeter.

Their Fathers Never Spoke of the War. Their Children Want to Know Why.

NEW ORLEANS — All his life, Joseph Griesser hungered to hear the story of his father’s Army service in World War II.

What he had were vague outlines: that Lt. Frank Griesser had splashed onto Omaha Beach on D-Day; that his lifelong pronounced limp had come from an artillery blast. But the details? They remained largely unspoken until the day his father died in 1999, leaving Mr. Griesser wishing he knew more.

“He never talked about it; I just knew he was injured in the war,” said Mr. Griesser, who lives in Stone Harbor, N.J. “We went to see the movie ‘The Longest Day’ together, but that was pretty much the extent of our conversation about the war. I think he just wanted to put it behind him.”

Many of the Americans who fought to crush the Axis in World War II came home feeling the same way — so many, in fact, that those lauded as the Greatest Generation might just as easily be called the Quietest.

Where did they serve? What did they do and see? Spouses and children often learned not to ask. And by now, most no longer have the chance: Fewer than 3 percent of the 16 million American veterans of the war are still alive, and all are in their 90s or beyond.

But that has not kept their children and grandchildren from wanting to know their stories, especially as the 75th anniversaries of the D-Day invasion and the other triumphs of the war’s final year have neared. And a growing number of them are turning to experts to help glean what they can from cryptic, yellowed military records.

“We have people calling every day to try to find out about their fathers,” said Tanja Spitzer, a researcher at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. “They regret that they didn’t do anything when their parents were alive. We get a lot of apologizing about it. For them, it is very emotional.”

Ms. Spitzer tells them it is not too late. Among the nation’s many staggering accomplishments in World War II were the billions of pages of personnel files that War Department and Navy clerks amassed to keep track of everyone in uniform. Most of those records still exist, stored in a climate-controlled facility in St. Louis by the National Archives and Records Administration.

The repository is immense, with enough boxes of files to stretch more than 545 miles. The boxes hold everything from the mundane, like payrolls and medical screening forms, to the heart-tugging: photos of young recruits, letters from worried mothers, medal citations. Researchers can use them to recreate the individual stories that many troops never told.

“We can tell a lot,” Ms. Spitzer said. “If you know what you are looking for, you can really create a full picture.”

[Read about researchers in France digging up the physical remains of the Normandy invasion.]

Responding to the growing interest, the museum created a research team this year focused solely on piecing together profiles of veterans from the archives, joining an array of military historians-for-hire who work with families like the Griessers.

“It’s a lot of sons and daughters, wishing they had the conversations that were too painful to have when their fathers were still alive,” said William Beigel, an independent historian in Redondo Beach, Calif., who has been researching World War II veterans for 20 years. He said demand has been surging as the ranks of living veterans have dwindled, and he now gets as many as 25 requests a day.

“Sometimes they start to cry on the phone about how much they loved their dad, and how he had horrible nightmares, but would never talk about it,” he said.

Mr. Beigel was able to document the daily movements of Mr. Griesser’s father from the Normandy beaches through the vicious fighting in the hedgerow country to the east, where he was decorated for valor and wounded by the blast of a German artillery shell.

Using that information, Mr. Griesser and his family traveled to France in May to retrace his father’s steps, and he plans to make a documentary about the trip for his family to pass down.

“It was very moving to be on the exact spot where he had been, and to think about how hard they really had it,” Mr. Griesser said.

The usual starting point for the research is the repository in St. Louis, a vast building crowded with more than six acres of shelves stacked 29 feet high. “It looks almost exactly like the last scene in ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’: endless shelves of stuff,” said Eric Kilgore, the research room supervisor.

The archives once held a file for nearly every veteran who served in either world war. But in July 1973, a fire broke out in the stacks that took firefighters four days to extinguish. Millions of documents were burned; millions more were left soaking wet, and soon began to molder in the muggy Missouri heat.

Navy and Marine Corps records were unharmed, but an estimated 80 percent of all Army records from World War II were ruined. Archivists have tried to reconstruct some files by drawing from other sources, but they say millions are lost forever.

“Sometimes, everything was destroyed but a name on a payroll,” said Dan Olmsted, a researcher at the World War II museum. “But fire is funny. Sometimes files that were in the middle of the fire were spared.”

That makes file requests on Army veterans something of a dice roll. But Mr. Olmsted said he has often pored over pages half-eaten by flames and rumpled by water damage and still been able to make out the vital details of a soldier’s life.

Anyone can view World War II personnel records at the St. Louis archive without charge. But the documents are often laced with military jargon and abbreviations that can be tough for a layman to decipher.

“You might as well be reading ancient Sumerian,” said Robert Citino, a historian who directs the research program at the museum.

Skilled researchers, he said, can interpret the personnel files and combine them with other records, like the commanders’ daily reports that amounted to a diary of each fighting unit, to weave a narrative of where soldiers went and what they did, sometimes in striking detail.

Their services come at a cost. Simply having a researcher pull and scan a service member’s file from the National Archives costs about $100. Combing other records to flesh out a narrative can run to many times that. For $2,500, the museum team will assemble a bound biography of a service member that includes historical context along with whatever photos and records are in the archives.

Many descendants say that finally knowing their relative’s story is worth the price.

Dolores Milhous remembers her father, Lt. James E. Robinson Jr., only as the tall man who came through the screen door and hoisted her onto his shoulders shortly before he shipped out. When he was killed in combat in the spring of 1945, she was 2 years old.

“Mother always talked about him,” said Ms. Milhous, 76, who lives in Dallas. “But there was so much I didn’t know — things I wished I asked before Mother passed away, but I hesitated because it made her so sad.”

Knowing that the memory of her father would only erode further as it was passed down to her five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, she asked the museum researchers to look for his file.

They returned with a stack of 240 partially burned pages from the archive, detailing a stunning story she had known in outline but not detail: Her father, a slight 25-year-old with a slim mustache and a Texas accent, had turned the tide in a battle involving thousands of men, and was posthumously awarded the military’s highest award for heroism, the Medal of Honor.

As an Army forward observer, Lieutenant Robinson’s job was to work his way up close to enemy positions and radio in coordinates for artillery strikes. In April 1945, his infantry regiment had pushed deep into Germany and was crossing a river when it ran into tough resistance: 1,800 men from an SS Panzer division, dug in on high ground.

His company of about 100 men attacked across an open field, but the Germans hit back hard. They attacked again before dawn the next day, but the SS troops were ready, raking them with machine-gun fire and pounding them with mortars. By noon, half the company was dead or wounded, and the rest were pinned down. At that crucial moment, the company commander was shot in the head by a sniper.

That left Lieutenant Robinson, who had next to no leadership experience, in command.

“Fully aware of the hopelessness of the situation, knowing that if the company remained in that position they would be annihilated in a very short time, he would have been justified in withdrawing,” read a singed report in the file, typed by a sergeant shortly after the battle. Instead, Lieutenant Robinson, “with complete disregard for his personal safety, amid the deadly hail of bullets and shells, gallantly and courageously rose to his feet and coolly walked among the men, shouting encouragement,” the report said.

He led a charge up the hill, jumping into enemy trenches and killing 10 German soldiers at close range, records showed. The company rallied behind him and overran the position.

Though the unit was down to just one-quarter strength, the lieutenant urged the men on to rout the enemy from a nearby village. At its edge, an enemy mortar round exploded next to him, sending hot shrapnel through his larynx.

Bleeding down his chest and barely able to speak, Lieutenant Robinson refused first aid and continued for hours to call in artillery strikes. At sunset, with the Germans finally driven off, he walked wordlessly back to the closest aid station, a mile and a half away. He died on an operating table a few hours later.

Ms. Milhous had heard as a child that her father was a hero, but the archive’s detailed records filled in the gaps, reassured her that the stories were more than just legends, and gave her something concrete to pass down.

“It finally puts things to rest,” she said. “And I can rest too, knowing his memory is preserved.”

Military Awards and Decorations

En Español

The National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) does not issue service medals; that is a function of each military service department. Requests for the issuance or replacement of military service medals, decorations and awards should be directed to the specific branch of the military in which the veteran served. However, for cases involving Air Force and Army personnel (click here for exceptions), the NPRC will verify the awards to which a veteran is entitled and forward the request along with the records verification to the appropriate service department for issuance of the medals. Use the addresses listed below, and mail your request accordingly.

How Do I Request Military Awards and Decorations?

For the Veteran: in general, the military services will work replacement medal requests for the veteran at no cost. This includes family members with the signed authorization of the veteran.

For the Next-of-Kin: the process (and cost) for replacement medals requests differs among the service branches and is dependent upon who is requesting the medal, particularly if the request involves an archival record. Click here for details.

For the General Public: if the service member separated from military service before 1959, the public may purchase a copy of the veteran's Official Military Personnel File (OMPF) to determine the awards due and obtain the medals from a commercial source. If the service member separated after 1959, the public may request such information from the OMPF via the Freedom of Information Act (see Access to OMPFs by the General Public).

| ARMY | |

|---|---|

| Where to write for medals | National Personnel Records Center 1 Archives Drive St. Louis, MO 63138 or REQUEST MEDALS ONLINE! |

| Where medals are mailed from | U.S. Army TACOM Clothing and Heraldry (PSID) P.O. Box 57997 Philadelphia, PA 19111-7997 |

| Where to write in case of a problem or an appeal | U.S. Army Human Resources Command Soldier Program and Services Division - Awards and Decorations Branch ATTN: AHRC-PDP-A 1600 Spearhead Division Avenue, Dept 480 Fort Knox, KY 40122-5408 |

| AIR FORCE (includes Army Air Corps & Army Air Forces) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Where to write for medals | National Personnel Records Center 1 Archives Drive St. Louis, MO 63138 or REQUEST MEDALS ONLINE! | ||||

| Where medals are mailed from, and where to write in case of a problem or an appeal |

| ||||

| NAVY | |

|---|---|

| Where to write for medals | National Personnel Record Center

|

| Where medals are mailed from | Navy Personnel Command PERS 312 5751 Honor Drive Building 769 Room 158 Millington, TN 38055-3120 |

| Where to write in case of a problem or an appeal | Department of the Navy Chief of Naval Operations (DNS-35) 2000 Navy Pentagon Washington, DC 20350-2000 |

| MARINE CORPS | |

|---|---|

| Where to write for medals | National Personnel Record Center

|

| Where medals are mailed from | Navy Personnel Command PERS 312 5751 Honor Drive Building 769 Room 158 Millington, TN 38055-3120 |

| Where to write in case of a problem or an appeal | Commandant of the Marine Corps Military Awards Branch (MMMA) 2008 Elliot Road Quantico, VA 22134 |

| COAST GUARD | |

|---|---|

| Where to write for medals, and where medals are mailed from | Coast Guard Personnel Service Center |

| Where to write in case of a problem or an appeal | Commandant U.S. Coast Guard Medals and Awards Branch (PMP-4) Washington, DC 20593-0001 |

Important Information for the Next-of-Kin (NOK):

Who is the Next-of-Kin (NOK)?

- For the Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps & Coast Guard, the NOK is defined as: the un-remarried widow or widower, son, daughter, father, mother, brother or sister

- For the Army, the NOK is defined as: the surviving spouse, eldest child, father or mother, eldest sibling or eldest grandchild

If you do not meet the definition of NOK, you are considered a member of the general public.

How the type of record (archival or non-archival) affects NOK requests for medals:

The Official Military Personnel File (OMPF) is used to verify awards to which a veteran may be entitled. OMPFs are accessioned into the National Archives, and become archival, 62 years after the service member's separation from the military. This is a rolling date; hence, the current year, 2020, minus 62 years is 1958. Records with a discharge date of 1958 or prior are archival and are open to the public. Records with a discharge date of 1959 or after are non-archival and are maintained under the Federal Records Center program. Non-archival records are subject to access restrictions. As such, the veteran's date of separation (separation is defined as discharge, retirement or death in service) will affect how the request is processed. See below:

| NEXT-OF-KIN, MEDAL REQUESTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Veteran's Separation Date | Army, Navy, and Marine Corps | Air Force and Coast Guard | |

| If the veteran separated from military service before 1958 | Requests are accepted at Write to: National Personnel Records Center Or REQUEST MEDALS ONLINE! | These Services do not accept NOK archival requests. The NOK may purchase a copy of the veteran's OMPF to determine the awards due and obtain the medals from a commercial source | |

| If the veteran separated from military service after 1958 | Requests are accepted at Write to: National Personnel Records Center Or REQUEST MEDALS ONLINE! | Requests are accepted at Write to: National Personnel Records Center Or REQUEST MEDALS ONLINE! | |

Cold War Recognition Certificate:

In accordance with section 1084 of the Fiscal Year 1998 National Defense Authorization Act, the Secretary of Defense approved awarding Cold War Recognition Certificates to all members of the armed forces and qualified Federal government civilian personnel who faithfully served the United States during the Cold War era from September 2, 1945 to December 26, 1991.

What Service does the NPRC Provide?

The NPRC, upon request, will provide copies of DD-214s (or equivalent) or SF-50s to authorized requesters. These documents may be used to apply for the Certificate. For information on how to obtain a copy of your DD-214 (for military service personnel) or SF-50 (for Federal civilian personnel) see:

| MILITARY PERSONNEL RECORDS | CIVILIAN PERSONNEL RECORDS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| If the veteran separated from military service before 1958: CLICK HERE | If the veteran separated from military service after 1958: CLICK HERE | If the Federal civil servant's employment ended before 1952: CLICK HERE | If the Federal civil servant's employment ended after 1951: CLICK HERE |

How Do I apply for a Cold War Recognition Certificate?

While the NPRC provides proof of service and separation documents; the Center does not supply the Certificate itself, nor does it have the application form available. For more information concerning the application process visit the Cold War Recognition Certificate webpage.

What’s New in the learning combat in For Honor Archives?

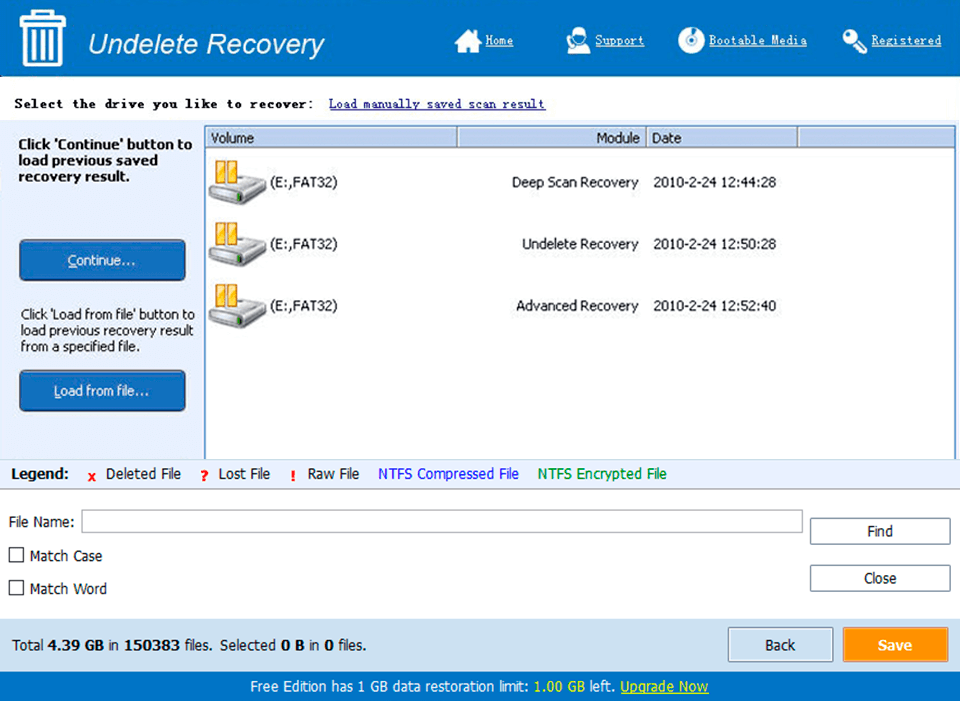

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Learning combat in For Honor Archives

- First, download the Learning combat in For Honor Archives

-

You can download its setup from given links: