Proprietary software Archives

Proprietary software Archives

Selection Criteria

Page history last edited by Lisa Spiro11 years, 7 months ago

No single archival management system will be appropriate for every archive, given the variation in technical support available at the institution and the need for particular features. Comparing archival management systems yields several key factors that distinguish them from each other. Here are some of the criteria that archives should consider in selecting an archival management system:

FOOTNOTES FOR SECTION 6 13 The University of Michigan is developing archival metrics: http://www.si.umich.edu/ArchivalMetrics/ |

Talk:Proprietary software

Concerns[edit]

This article is in a very bad state, for several reasons:

- NPOV: If it written from the perspective of free software / open source (sorry, but it is)

- Unclear/biased definition: The article seems to somewhat state that "Proprietary software is any software that fails to be "free software" or "open source software" " - I'm pretty sure people distributing so called "proprietary software" don't use that wording most of the time, neither users (instead using "commercial software" or "freeware" / "free software" when the software is gratis)

- Few (none?) reliable sources directly discussing what proprietary software is

- Original research and/or synthesis: The first reference, for example, links to an Apple EULA, but there is no mention there of "proprietary software"

- Proprietary formats/protocols: Many many "proprietary software" (closed source) programs don't use so called "proprietary formats". It is also perfectly possible for an open source program to read/write, for example, formats subject to patents (called "proprietary" by some). It should also be noted the article Proprietary format is also immensely biased.

- "Proprietary software is said to create greater commercial activity over free software, especially in regard to market revenues." - really??? Clearly biased and WP:WEASEL wording. In addition to that, it is pretty much common knowledge that proprietary/closed/commercial software generates much greater revenue. Even people like Richard Stallman (commonly considered on a more "extreme" side) perfectly admit this.

- In conclusion, the entire article is written in a certain POV against "proprietary software", so it is hard to pinpoint specific problems.

- "Richard Stallman says that proprietary software commonly contains "malicious features, such as spying on the users, restricting the users, back doors, and imposed upgrades" Really??? - I'm pretty suspicious of that claim, and I highly doubt it. Extra-ordinary claims require extra-ordinary proof (see WP:BURDEN). In addition, how can a man who thinks "proprietary software" is "evil", "user-subjugating" and something that "shackles" users be even considered as a proper reference?

Don't get me wrong, I perfectly admit I sympathize with the concepts of free software / open source, and I have no connection to any "software industry", but I can see this is clearly biased. --SF007 (talk) 18:48, 13 January 2012 (UTC)

- The critics of proprietary software, who I think invented the term, use it pejoratively. On the other hand those who create proprietary software - the software industry – commercialize their products largely by exercising these exclusive ownership rights. It seems like you want the article written from the industry's perspective, which wouldn't be right. It needs to balance these two major points of view, and any other important views on the subject.

- The article does this in some ways. For example it follows RMS' view that commercial software contains malicious features with software vendors' view that closed-source means more secure, an open-source response to that view, and a description of the industry practice of disclosing source code to governments to address their security concerns. It may not achieve perfect balance, but it certainly includes both industry points of view and critical points of view, with the goal of allowing the reader to form a view of her/his own.

- Here are responses to your substantive points:

- The article seems to somewhat state that "Proprietary software is any software that fails to be "free software" or "open source software".

- It attributes that definition to "proponents of free and open source software." There is a primary source reference of a prominent such entity. I think the statement as attributed is true. Is the problem that it's synth?

- "I'm pretty sure people distributing so called "proprietary software" don't use that wording most of the time, neither users (instead using "commercial software" or "freeware" / "free software" when the software is gratis)

- I agree, and that's an important point, but it's about usage, not definition. The article touches on the matter in Proprietary software#Pricing_and_economics, which links to commercial software, freeware, and free software. I added a brief mention to the lead.

- Few (none?) reliable sources directly discussing what proprietary software is

- Also a good point. There should be more secondary sources which directly address the definition. Stanford Law Review & Webster's Computer & Internet Dictionary are two which do.

- Original research and/or synthesis: The first reference, for example, links to an Apple EULA, but there is no mention there of "proprietary software"

- It was an improper use of the source so I removed it. I don't think the statement it had supported is likely to be challenged: "The licensee is given the right to use the software under certain conditions, while restricted from other uses, such as modification, further distribution, or reverse engineering."

- Many many "proprietary software" (closed source) programs don't use so called "proprietary formats".

- That is a missing point of view, but apart from text editors, HTML editors, web browsers, and some scientific software I'm hard-pressed to think of prominent examples.

- It is also perfectly possible for an open source program to read/write, for example, formats subject to patents (called "proprietary" by some).

- If some aspect of reading or writing the format is patented, it would be technically but not legally possible to do so without licensing the patent.

- It should also be noted the article Proprietary format is also immensely biased.

- Maybe so. I toned down the language and removed the dependence on that article's definition and the inline wikilinks. Also: [1]

- "Proprietary software is said to create greater commercial activity over free software, especially in regard to market revenues." - really? really??? Clearly biased and WP:WEASEL wording. In addition to that, it is pretty much common knowledge that proprietary/closed/commercial software generates much greater revenue. Even people like Richard Stallman (commonly considered on a more "extreme" side) perfectly admit this.

- Did you misread the sentence? It says proprietary software creates greater commercial opportunities and greater revenues. The sentence was weaselly and hardly brilliant, but surely you can see it was trying to say exactly what you're saying. It wasn't in the source, though. I removed the sentence and the citation. The perspective needs to be put back in, using a better source.

- "Richard Stallman says that proprietary software commonly contains "malicious features, such as spying on the users, restricting the users, back doors, and imposed upgrades" Really?????? - I'm pretty suspicious of that claim, and I highly doubt it. Extra-ordinary claims require extra-ordinary proof (see WP:BURDEN).

- WP:REDFLAG seems to be the relevant section, which says "any exceptional claim requires high-quality sources." The quote is directly from an article RMS wrote and the ACM published, which is as reputable and high-quality as a source can be. It's hardly surprising that Stallman said this. It seems to meet the burden of evidence for an exceptional claim.

- In addition, how can a man who thinks "proprietary software" is "evil", "user-subjugating" and something that "shackles" users by even considered as a reference?

- His perspective belongs in the article because he's prominent critic. The article doesn't state his view as fact.

- The article seems to somewhat state that "Proprietary software is any software that fails to be "free software" or "open source software".

- – Pnm (talk) 22:47, 13 January 2012 (UTC)

- Hello Pnm, I appreciate your attention. First of all, I have no interest in writing this from the perspective of the industry, like I said, I love FOSS, but I certainly think the article is far from "neutral", giving undue weight to the negative aspects of "proprietary software". In a way, I think it might be impossible to have a neutral article due to the already "biased" naming, in a way, it's like trying to write an article about gay people but with the title "faggots" or "sodomy" or an article about feminists titled "feminazi movement": you simply can't have a neutral coverage. Anyway, I will create new sections to discuss specific problems, so i will not reply to everything here. I would just like to add that my opinion regarding the sentence "Proprietary software is said to create greater commercial activity over free software, especially in regard to market revenues." was mis-interpreted (totally my fault), I was simply pointing out this is an "obvious" thing, and therefore the expression "is said to" was an unnecessary expression of doubt.--SF007 (talk) 00:50, 14 March 2012 (UTC)

Note: This article also seems incompatible with the definitions at Merriam Webster --SF007 (talk) 01:42, 14 March 2012 (UTC)

- In other words, the term "proprietary" is apparently used in it's subordinating third level meaning. This is my impression too. With the primary meaning of "proprietary", programs like "gtar" must be seen as proprietary as gtar usually creates "tar-archives that do not follow even low level structuring rules for tar archives and thus cannot be unpacked by standard tar implementations that do not know about the deviations used by gtar. I therefore vote for moving the article to a more descriptive name. Schily (talk) 12:56, 27 November 2014 (UTC)

—

I have to add to the criticisms alreeady stated.

Right now the introduction is:

That makes the term uselss as that applies to all software that is not public domain or absolutely trivial as the threshold for protection by copyright is quite low. So the statement can be reduced to:

"Proprietary software is omputer software to which someone holds some kind of intellectual property right." That includes all copylefted (ugh! that word) stuff, too, otherwise there would be no basis for making legal claims, thus making all of that proprietary, too, by current definition in the article.

So, right now the aricle is definitely biased towards using proprietary pejoratively making the whole thing a propaganda piece and not useful information. I am of the opinion that the whole article is unnecessary and worthy of deletion as right now the word proprietary applied to software gives no additional information. The word just takes up space but conveys no meaning. 92.229.87.146 (talk) 15:39, 4 September 2016 (UTC

"fringe theory"[edit]

The article currently contains the sentence:

Richard Stallman says that proprietary software commonly contains "malicious features, such as spying on the users, restricting the users, back doors, and imposed upgrades."This is problematic on various levels:

- NPOV - "neutral point of view (NPOV) means representing [...] all significant views that have been published by reliable sources" - Stallman's view is hardly a "significant view"

- undue weight - "Generally, the views of tiny minorities should not be included at all"

- It is a Fringe theory / conspiracy theory, backed by absolutely zero evidence (from WP:FRINGE):

"An idea that is not broadly supported by scholarship in its field must not be given undue weight in an article about a mainstream idea,[1] and reliable sources must be cited that affirm the relationship of the marginal idea to the mainstream idea in a serious and substantial manner."

"We use the term fringe theory in a very broad sense to describe ideas that depart significantly from the prevailing or mainstream view in its particular field."

A conjecture that has not received critical review from the scientific community or that has been rejected may be included in an article about a scientific subject only if other high-quality reliable sources discuss it as an alternative position.

"Care should be taken with journals that exist mainly to promote a particular viewpoint. Journals that are not peer reviewed by the wider academic community should not be considered reliable, except to show the views of the groups represented by those journals." - The FSF is clearly an organization with certain political views, clearly not a reliable source.

"Quotes that are controversial or potentially misleading need to be properly contextualized to avoid unintentional endorsement or deprecation. What is more, just because a quote is accurate and verifiably attributed to a particular source does not mean that the quote must necessarily be included in an article"

"The best sources to use when describing fringe theories, and in determining their notability and prominence, are independent reliable sources."

"Points that are not discussed in independent sources should not be given any space in articles."

"Independent sources are also necessary to determine the relationship of a fringe theory to mainstream scholarly discourse." ____

User Pnm stated "His perspective belongs in the article because he's prominent critic.", but that is highly debatable, is his view (the particular one about spyware/backdoor) discussed in reliable sources? Do we have reliable sources that support he is a "prominent critic"? It should also be noted that being a "prominent critic", by itself, is not a valid rationale for inclusion. --SF007 (talk) 01:35, 14 March 2012 (UTC)

- Re-added the sentence. Its not perfect, but it is not in violation of WP:FRINGE (as the claim say's above). The idea that proprietary software can and some do include spyware/backdoor might be considered a fringe idea outside IT security community, but inside its a common discussed theme. Look at criticism about electronic voting (Bruce Schneier and CCC has some good articles) for examples where discussions about closed software and backdoors are talked about. There has also been discussion about backdoors in mobile phones, where android (open source) has been commonly argued to be more secure because its open source. For the concept in general, most open source projects that feature security common talks about open source as being more secure since users can verify that the code does what the user want and nothing else (BSD, Firefox, tor, android (again)). In more broadly context, we have the Security_through_obscurity concept, where the "fringe" view of the security community is presented to the contrast of the common belief, and there is the meme "Given enough eyeballs all bugs are shallow" which has also been commonly discussed in the area of security bugs for Firefox (compared mostly to IE).

- In general, the sentence should be there, but like i said earlier, it can be improved. The word "common" in the sentence, sound fringe/weasel/plain wrong, but the whole thing is presented as a quote and thus removing that word would be a form of misrepresenting. One could try to combine tor/firefox/bsd/stallman/e-voting-criticism into its own paragraph writen not as quotations. If I have the time/find all the sources I need, I might do it, but I rather have a imperfect sentence than none at all. Belorn (talk) 04:20, 20 March 2012 (UTC)

Proprietary not the Same As Closed Source[edit]

I'm unconvinced these are the same things, closed source software is is simply software where the source code is not made available, and typically in the case of Commercial closed source software (but not necessarily) users of the software are expected to pay for a license to use the software and are not allowed to reverse engineer it, but that is it.

With Proprietary software you are adding an extra layer of restriction that usually takes the form of locks in to make it difficult to swap to a different piece of software, or require a yearly payment to be made but this is only a small percentage of closed source software. For example Microsoft Word launched with its own document format (.doc) that was not documented making it difficult to swap documents with other word procccessers, this is a proprietary format and in using it it makes Word proprietary software. But why should another closed source word processer that use open document formats be labelled proprietary. it is important to make the distinction between closed source and proprietary software

An interesting article here http://breakthroughanalysis.com/2013/12/22/what-exactly-is-proprietary-software-and-why-is-anything-not-open-source-not-the-answer/

Ijabz (talk) 11:01, 27 March 2014 (UTC)

- These are partially the same, but you're saying something that goes against your (other) sayings. First of all because Word is closed source and asks money, that's what it makes proprietary and not the closed parts.

- Closed source is (almost) always proprietary, since you need to pay for this kind of software, the developer holds license for it and/or can only access the code. According to GNU proprietary is only closed source software. Proprietary software is software you can't redistribute.

- What matters is that, against your saying, again, open source using reverse engineered proprietary software is still open source, but proprietary or closed source software containing open source, must release the free/open source software parts included and is still prorietary/closed source.

- Also FOSS isn't always "free" as in gratis, but it is as in feel free to redistribute.

- Most companies however discribe the FOSS "free" as in gratis, but that's not true, looking at Red Hat, some companies make money with FOSS.

- If they launched it closed source and ask money for it or make it limited, then it is proprietary, you can't make FOSS limited, so FOSS is never proprietary.

- The link you're referencing to is (almost) the same as this one, http://www.pcworld.com/article/243136/open_source_vs_proprietary_software.html

- CedricO (talk) 11:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

Neutrality[edit]

This article seems excessively slanted toward the FOSS movement. While there are a few paragraphs in the article discussing reasoning from supporters of proprietary software, overall the article reads in a very pro-free software light, especially in it's use of terminology regarding software rights. --Nathan2055talk - contribs 02:11, 22 July 2015 (UTC)

- I have never edited this article before. I subscribe to the views of the FOSS movement (you can witness it in my contributions page) and I agree that this article may be lacking coverage from the point of view of proprietary software users and developers themselves. Feel in total concession to add information on the views supporting proprietary software. It may be good to separate pros and cons in different sections. Regarding slanted wording, the use of more neutral terms would also be appreciated. Another stylistic option that allows for the inclusion of strident views in controversies is to simple cite them instead of adopting them and biasing the article. For instance, "According to ... proprietary software is ..." --isacdaavid 16:28, 30 July 2015 (UTC)

- Keep in mind WP:STRUCTURE, though. I don't think it would be a good idea to separate pros and cons into different sections. We should try to achieve a more neutral text by folding the debate into the narrative, rather than isolating different points of view into sections that ignore or fight against each other. --Dodi 8238 (talk) 09:17, 14 October 2015 (UTC)

External links modified[edit]

Hello fellow Wikipedians,

I have just added archive links to one external link on Proprietary software. Please take a moment to review my edit. If necessary, add after the link to keep me from modifying it. Alternatively, you can add to keep me off the page altogether. I made the following changes:

When you have finished reviewing my changes, please set the checked parameter below to true to let others know.

YAn editor has reviewed this edit and fixed any errors that were found.

YAn editor has reviewed this edit and fixed any errors that were found.

- If you have discovered URLs which were erroneously considered dead by the bot, you can report them with this tool.

- If you found an error with any archives or the URLs themselves, you can fix them with this tool.

Cheers.—cyberbot IITalk to my owner:Online 22:54, 24 January 2016 (UTC)

- Got some SUN vs. MS PDF, okay. – 18:03, 12 April 2016 (UTC)

External links modified[edit]

Hello fellow Wikipedians,

I have just added archive links to one external link on Proprietary software. Please take a moment to review my edit. If necessary, add after the link to keep me from modifying it. Alternatively, you can add to keep me off the page altogether. I made the following changes:

When you have finished reviewing my changes, please set the checked parameter below to true to let others know.

NAn editor has determined that the edit contains an error somewhere. Please follow the instructions below and mark the to true

NAn editor has determined that the edit contains an error somewhere. Please follow the instructions below and mark the to true

- If you have discovered URLs which were erroneously considered dead by the bot, you can report them with this tool.

- If you found an error with any archives or the URLs themselves, you can fix them with this tool.

Cheers.—cyberbot IITalk to my owner:Online 03:50, 24 February 2016 (UTC)

- Good bot-edit, bad archive URL, added . – 17:55, 12 April 2016 (UTC)

pregunta[edit]

porque son tan gachos a desalma2?:):):) saludos target ..ah control Re Motá? luzbrillith (talk) 16:32, 12 April 2016 (UTC)

This may include applications that you have on disc or movies that aren't so crucial but use a lot of storage space. ppTime Machine does not include the option to automatically exclude all files of a certain type or name.

It essentially backs up your entire hard drive and excludes only those folders and files that you have found and added to the exclusion list.

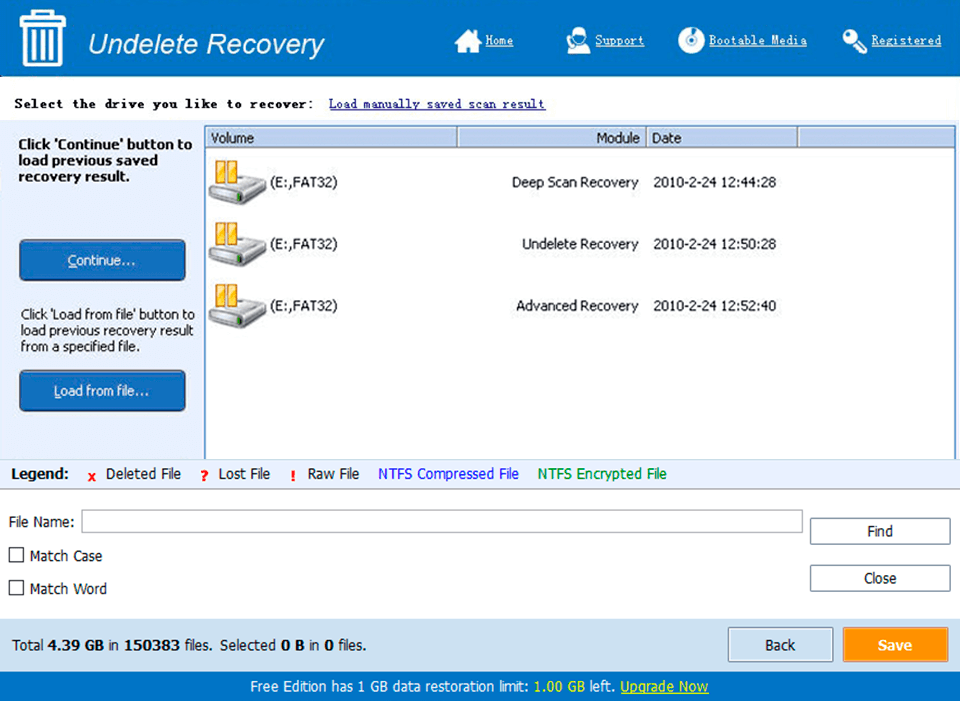

.What’s New in the Proprietary software Archives?

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Proprietary software Archives

- First, download the Proprietary software Archives

-

You can download its setup from given links: